The danger of available ideas

June 7, 2022

My freshman year, I was required to take a Health class as an elective. The class attempted to cover sensitive topics, such as mental health, good decision making, etc. The class had its highs and lows, but one unit stuck out as particularly egregious. That is, the drug abuse unit.

The unit on drug abuse, like any typical health class, was intended to teach us why NOT to use any of the mentioned substances. Oddly enough, at times, it seemed to have the opposite effect.

We were shown a slideshow covering many of the most infamous substances: cocaine, MDMA, heroin, anything one might think of. The thing that struck me as strange was that although the negative consequences were emphasized, the slideshow also chose to include an expansive list of each drug’s side effects. The unit went into great detail about the vivid hallucinations, dopamine rushes, and positive feelings that users typically experience after using a substance.

The unit did not by any means encourage us to take any illegal substance, and in fact heavily advised against it. But I remember briefly thinking, during the description of cocaine’s powerful and long lasting highs, “That sounds kinda fun, actually.”

Clearly, not the intended message.

Now, I am by no means a substance abuser of any kind. Outside of that moment, cocaine usage is not something that frequently, if ever, crosses my mind. And the second I had that thought, I immediately dismissed it as ludicrous. But the fact that it even crossed my mind is indicative of a larger problem. And if it crossed my mind, what about the student who is already using a substance and is far more likely than I to try a worse one?

This anecdote is a long-winded way of introducing the concept of available ideas. The act of giving someone an available idea is simple. A typically well-meaning person or piece of media mentions a negative idea, often to make a point, and it makes the idea available in the receiver’s mind. For instance, although the drug slideshow meant well, its consequential available idea was “That sounds kinda fun, actually.”

Usually, the receiver hasn’t considered this idea before. Unfortunately, now that that idea is available in their mind, regardless of context, they may actually be more likely to do it. Had I not known about the intimate details of a cocaine high, I would be far less likely to do it. While it is extremely unlikely, nay impossible, that I will ever use cocaine, having extensive knowledge about all the positive side effects does spark a curiosity that the lesson definitely did not intend to spark. I even joked with a few of my friends about this, and found that that split second idea was overwhelmingly common amongst those of us in the class.

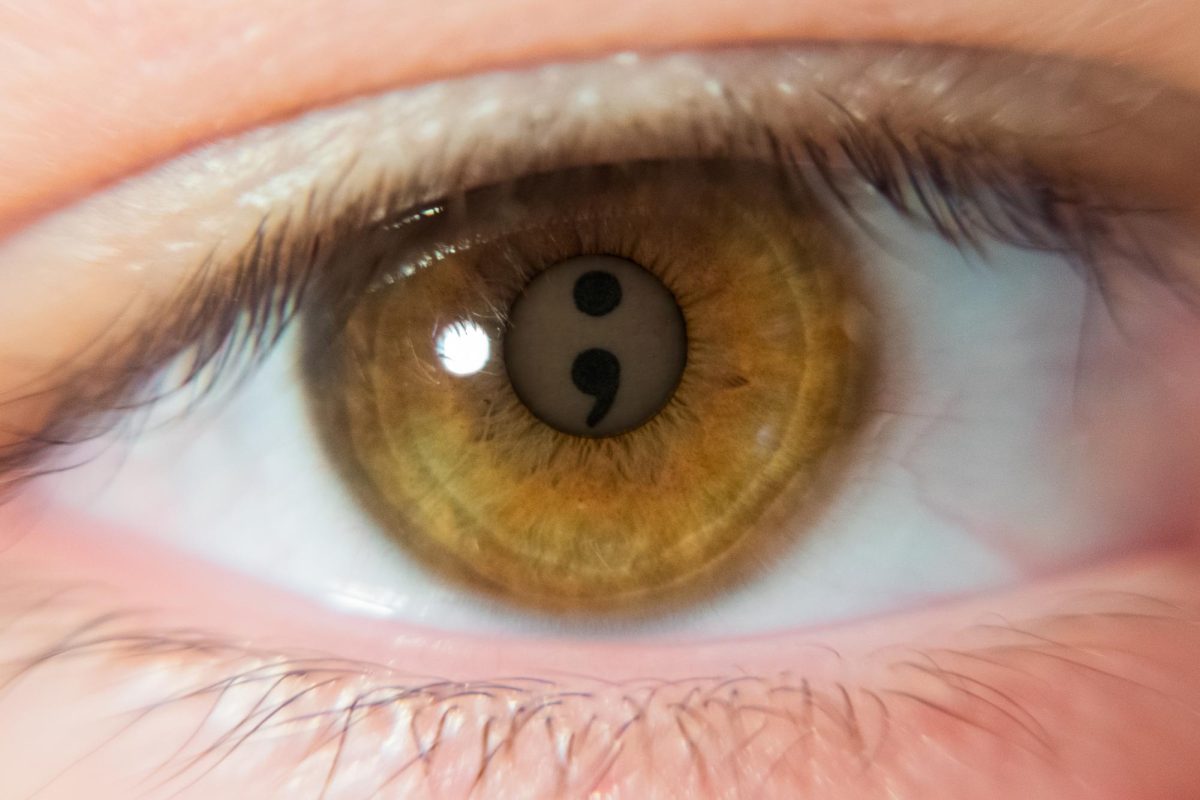

A similar incident occurred when my high school paid a man to come give a lecture about his history with mental illness and his failed suicide attempt. Though undoubtedly well-meaning, the lecture had a similar negative effect to the health class slideshow – it introduced an available idea. Obviously, I won’t be detailing the lecturer’s suicide attempt, as that would undermine my point. However, during the lecture, a similar thought crossed my mind – “That seems like a pretty easy way to do that, if I wanted to.”

A suicidal kid usually won’t care about the rest of the intended message of a story like that, regardless of how in-depth or positive it is. Someone who is actively suicidal and/or severely depressed will often hear about someone’s self harm methods or someone’s suicide plan, and take inspiration.

And to top it off, both the health class and the mental health lecture lacked something significant – detailed information on recovery.

Of course, the concept of rehab was mentioned in my health class. Of course, the lecturer gave the usual spiel about crisis hotlines and reaching out to others if you’re in a bad place. But what these things often lack is information on what happens AFTER you dial that hotline, or check yourself into rehab, or seek a therapist, or any number of things.

I spoke to a student who wished to remain anonymous about their recovery process from an eating disorder. “Based on what I learned in health class, I believed that everything would click all at once and suddenly it would become easy to recover from an eating disorder; that once I was ‘sick enough’, I would be able to move on,” The anonymous student went through a recovery program, and has said they had no idea what to expect from it. “I wish I knew having an eating disorder isn’t the hardest part, recovering from it is.”

This person’s story is tragically common. It is all too common for students to avoid seeking formal treatment for things like a serious mental illness or an eating disorder because they don’t know what to expect from treatment. Often, it seems as though this false narrative is pushed that someone has to hit rock bottom in order to enter treatment. We are taught that treatment is for those who have nowhere else to go, for people who are near-irreparably damaged by their addiction or mental illness.

If we insist on educating our young people about what happens after you take ecstasy or LSD, we should at minimum provide them with information about what happens after the fallout.

Of course, not every topic is exactly the same. There are some topics, like sex ed, where in-depth explorations are important. But the principle holds. If we are going to educate people about something, there should be an equal and complete emphasis on what happens after it goes wrong.

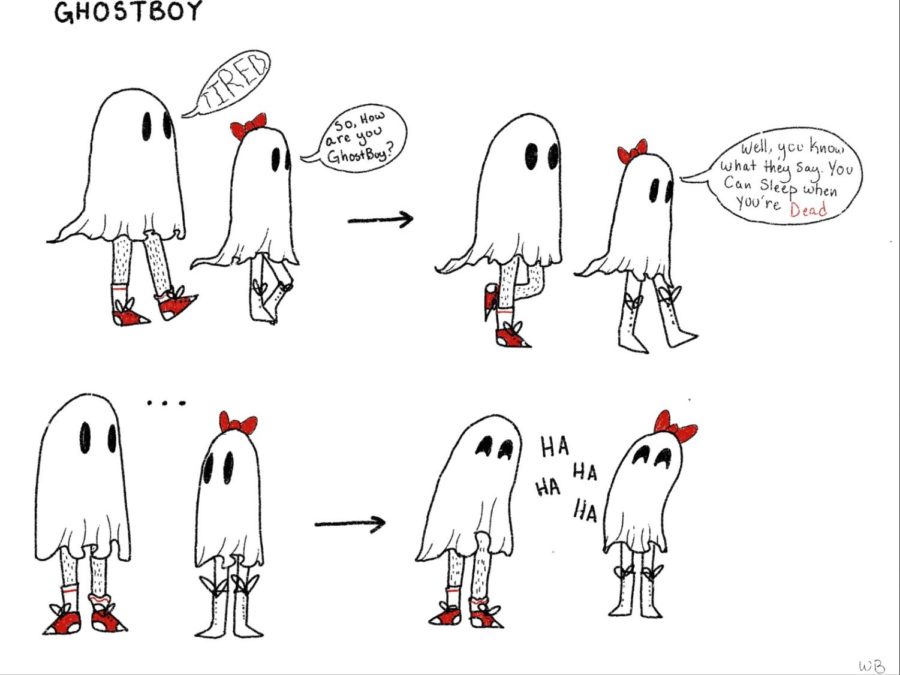

Young people are already bombarded with available ideas online constantly. Blogs or accounts that claim to be “pro-recovery” will post detailed accounts of someone’s struggle with an eating disorder or self-harm. It is incredibly common for these posts to detail people’s former methods as “things not to do”. We see posts of people bragging about the “amazing high” they got from their last vape hit and a part of us thinks, “That looks kinda fun”. We see a clearly unhealthy woman’s detailed workout and diet routine, and a part of us thinks, “I want to look like that”.

At the end of the day, as harsh as it sounds, intent does not matter. Lectures and units and even simple allusions like these can provide a dangerous inspiration to those already struggling. In the age of social media, it is easier than ever to get this dangerous inspiration. So, if it’s unnecessary and even harmful to a kid to teach them about how amazing the side effects of opioids are, why do it at all?