Two towns, one school

History, harmony, and the many reasons to regionalize

A sailboat in Smith Cove near Rocky Neck in Gloucester Harbor

As with any two towns, the relationship between Gloucester and Rockport is a veritable soup of anthropology. But as the 21st century begins to bring about change in the demographic and economic situations of these two municipalities, the soup is becoming increasingly important to strain. Why is that? It’s because of our public school systems.

Regionalization, the combination of Rockport and Gloucester public schools into a single district, is a possibility that’s far closer to reality than people realize. It’s a polarizing issue that involves everything from economics to educational philosophy, but resistance to the prospect often goes deeper than financial unease. It’s a matter of identity. With this in mind, the question becomes: How did Rockport and Gloucester become so different in the first place? And why is it still affecting us today?

Before we answer that, let’s look at the facts of regionalization.

There are two main reasons that the combination of Gloucester and Rockport is a viable possibility. One is money and the other is enrollment.

“The town of Rockport is about to run into a financial crunch,” said school committee member Joel Favazza, “They [soon] won’t be able to sustain their school budget without increasing their taxes beyond what the law allows. Gloucester is likewise faced with budgetary constraints.”

Combining the schools could help alleviate this financial stress. This is especially true because no new buildings would need to be constructed in this merge. GHS and O’Maley both have plenty of empty classrooms; between the two districts all students could easily be accommodated.

“If we were to regionalize with Rockport there would be enough room at Rockport to not rebuild Beeman and Plum Cove,” said Favazza, “[That would save the district] 70 million dollars. You would have West Parish, [the new] EGS/Veterans, and one [elementary school] at Rockport. There are already empty classrooms at [Gloucester] middle and high schools. We need to take advantage of the buildings we already have on the island. Rather than spending tens of thousands on new facilities, we should use that money to infuse the ones we have with resources.”

Of course none of this is set in stone. High school could just as easily be held in Rockport rather than Gloucester, and the same is true of all grade levels.

Beyond that, Gloucester and Rockport are both seeing a demographic shift. “As Cape Ann becomes too expensive to raise a family, Gloucester is re-positioning toward a retirement community. The average age of citizens is increasing every year and the number of school children is decreasing,” said Favazza.

Low enrollment is a big problem in both towns. Compared to the 2002-2003 school year, Gloucester Public Schools educate 30 percent less students. Rockport has seen 24 percent decrease, and of the 76 percent that remain, 25 percent are from Gloucester in the first place. The combined populations of GHS and RHS today are less than the population of GHS alone in 2002.

Additionally, it would allow both towns to provide a more well-rounded education.

“Gloucester has lots of resources for kids who need specialized services as well as a [great] STEM education program. Rockport does a much better job in arts and music education. One would hope we could take the [best of both worlds],” said Favazza.

Cape Ann has already seen success with regionalization.

“The same thing occurred with Manchester-Essex. It took a decade, but now they are a highly competitive and sought after district, “ said Favazza.

As it stands, both school systems have a lot to gain from the merge. Why is it then, that so many are against it? This is where our question comes into play: How did Rockport and Gloucester become so different in the first place? And why is it still affecting us today? The answer lies in history.

Gloucester and Rockport were at one point the same town. For many years, Rockport was not a settled area, but land set aside for the timber industry. When people began moving in during the early 1700s, Sandy Bay and Pigeon Cove were just two more Gloucester neighborhoods, like Lanesville or Magnolia. The split came mainly as a result of religious necessity. At the time, where you went to church was dictated by which parish you lived in.

According to longtime Gloucester resident and historian Mary Ellen Lepionka, “Church attendance was mandatory in the 17th and 18th centuries. Sandy Bay petitioned repeatedly to become a separate parish, which was finally granted in 1754. Sandy Bay and Pigeon Cove were previously part of the Third Parish in Annisquam and the people had to walk through Dogtown to get to church!”

The cultural identities of Gloucester and Rockport began on wildly different tracks soon after the split. Gloucester’s immigrant population grew relatively early in its history, while Rockport established itself as rather more homogeneous.

“Demographic differences were related to both ethnicity and social class,” said Lepionka. “By the time it was set off as a town in 1840, Rockport had developed as a rural WASPish summer resort for the wealthy, with a small-scale fishing and lobstering industry, while Gloucester had become more populated and urbanized and was sending out large fleets to the Grand Banks. People coming from Ireland, Scandinavia, Italy, Sicily, Portugal, and the Cape Verde Islands as immigrants to Gloucester at that time to work in the fisheries and quarries were not wealthy. Many fell victim to the usual prejudices against minorities.”

What does this have to do with regionalization? Historical events have affected the culture of the two municipalities, and, as a result, the way the two school districts function.

“Gloucester has greater diversity and a larger scale and therefore many cultures, more or less compartmentalized. It also has proportionally many more children in poverty and/or with special needs. Another difference relating to schools is Gloucester’s tendency to anti-intellectualism–a rejection or distrust of what is perceived as elitism or outside influence—again relating to social class. The Gloucester and Rockport school systems today reflect this difference–in size, staffing, curriculum, and performance, “ said Lepionka.

She is right about this.

Nearly all of the issues that people bring up at the mention of the merger have their roots in the differences above. However, many of them can be easily rebuked.

For example, the issue of size. Lots of Rockport parents subscribe to the philosophy that small schools better facilitate learning. This argument is perfectly legitimate. However, combining schools would allow for a larger budget that could accommodate more teachers. More teachers means smaller classes and a more intimate learning environment.

Size doesn’t really play a role in student life at the school-wide level; it plays a role at the classroom level.

Performance is another major concern, but it has a lot to do with stereotypes. In the recent past (a few decades ago) Gloucester did provide a very different, arguably worse, school experience than Rockport. But this is not the case anymore.

As Favazza explained: “4 out of 5 Gloucester elementary schools outperformed Rockport elementary on MCAS accountability [measures]. 3 out of 5 did more than twice as well. Thinking that Rockport provides a superior education (though it may have been true a decade ago) [is not true]. It has evened out; the districts are more similar than people realize.”

The social scene in Gloucester is also very different than it was in years past. Gloucester and Rockport student populations are somewhat similar, as evidenced by the (approximately) 202 Gloucester kids who attend Rockport schools. The main difference is in Gloucester’s high needs and ELL populations, which are considerably larger than Rockport’s.

As Favazza explained, “ For those fearful of the students populations [coming together, know] that they’re already integrated, we’ve just not acknowledged it. Twenty-five percent of students in Rockport are from Gloucester. [Our schools] kind of already have a mixed population.”

If we’re being honest though, the opposition seems to go deeper than logistics. It’s a matter of sentiment; of culture and tradition. Lepionka explained: “Gloucester and Rockport have been on different trajectories for a very long time, and their self-awareness as distinct polities has grown intergenerationally, transmitted within both family traditions and official histories. Descendants of immigrants are no longer minorities, but cultural and class differences, and resentments relating to them, persist to this day.”

Joseph Billante, a lifetime resident of Gloucester and graduate of GHS class of ‘62, put it best.

“There will be a clash of cultures, and that takes time [to smooth over].”

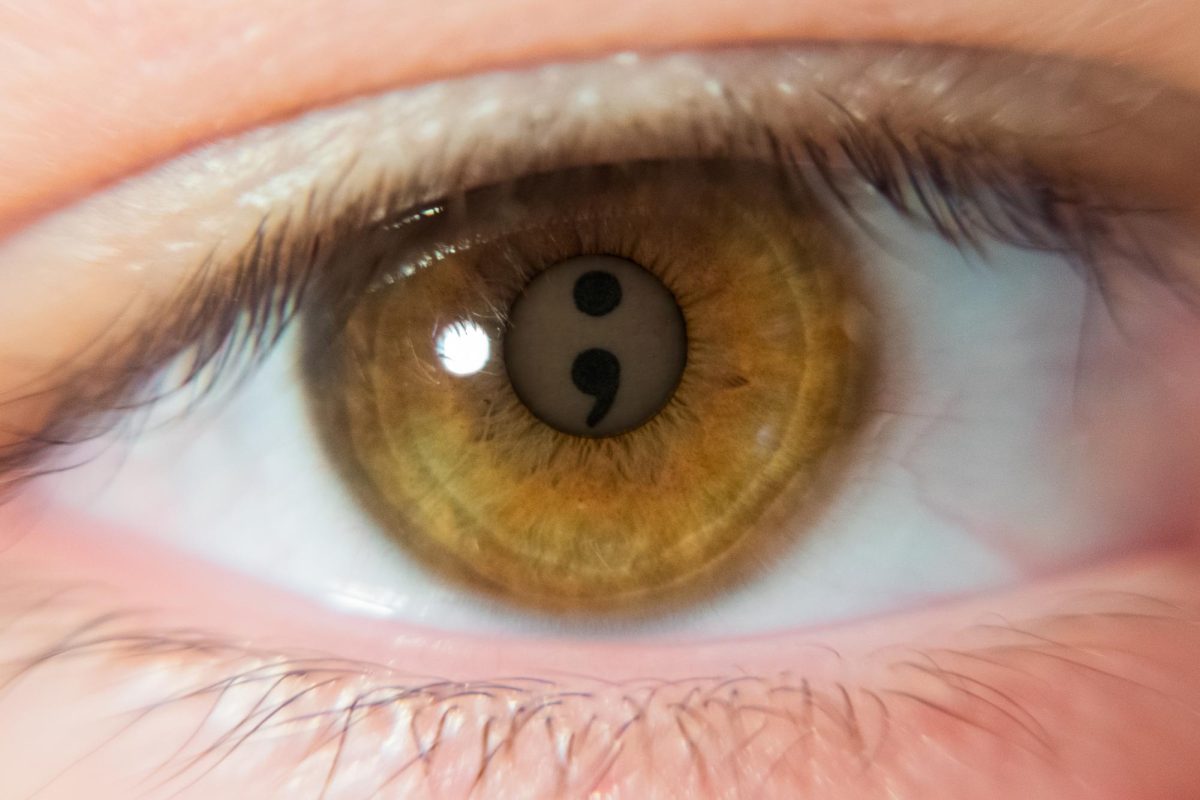

We cannot allow the past to get in the way of our children’s futures.

Mila Barry is in her fourth year at Gloucester High School, and her third year on the Gillnetter staff. Outside of writing for the newspaper, she’s...

Mila Barry is in her fourth year at Gloucester High School, and her third year on the Gillnetter staff. Outside of writing for the newspaper, she’s...

Tamsen Endicott • Dec 12, 2019 at 3:49 am

My paternal great-grandparents came to Gloucester from Newfoundland and Nova Scotia at the end of the 19th century, drawn by the fishing industry. My maternal great-grandparents and grandparents moved to Rockport during the Depression as an affordable place for my great-grandparents to retire and for my grandparents to start a family. The cultural differences exist between the communities but many, many families in Gloucester and Rockport are intertwined through generations of intermarriage.

Regionalization of the schools is the best way forward for both communities to provide the best education for all of our children. We should also consider a coordinated housing and land use policy that would enable more families to live on Cape Ann, and to protect our water and transportation infrastructure in the face of climate change.

Esther Young • Nov 27, 2019 at 4:31 pm

Rockport will never go for it. Should have been done years ago witj Manchester and Essex.

JD Herlihy • Nov 27, 2019 at 10:39 am

Well reasoned and written article. I commend the author on starting and extending this important discussion on the future of the educational system on Cape Ann. As a former Rockport resident, I agree the regionalization of the schools is a very important discussion. I have first hand witnessed the issues with perception and stereotypes mentioned in the article and agree wholeheartedly that they have limited the discussion on regionalizing the school system. I personally see a regionalized school as the logical and best future for both Rockport and Gloucester!

Caroline Enos • Nov 25, 2019 at 11:58 pm

Such a good analysis of this! Should be an interesting debate down the line too.