Weighing the risks: athletics and education in the COVID era

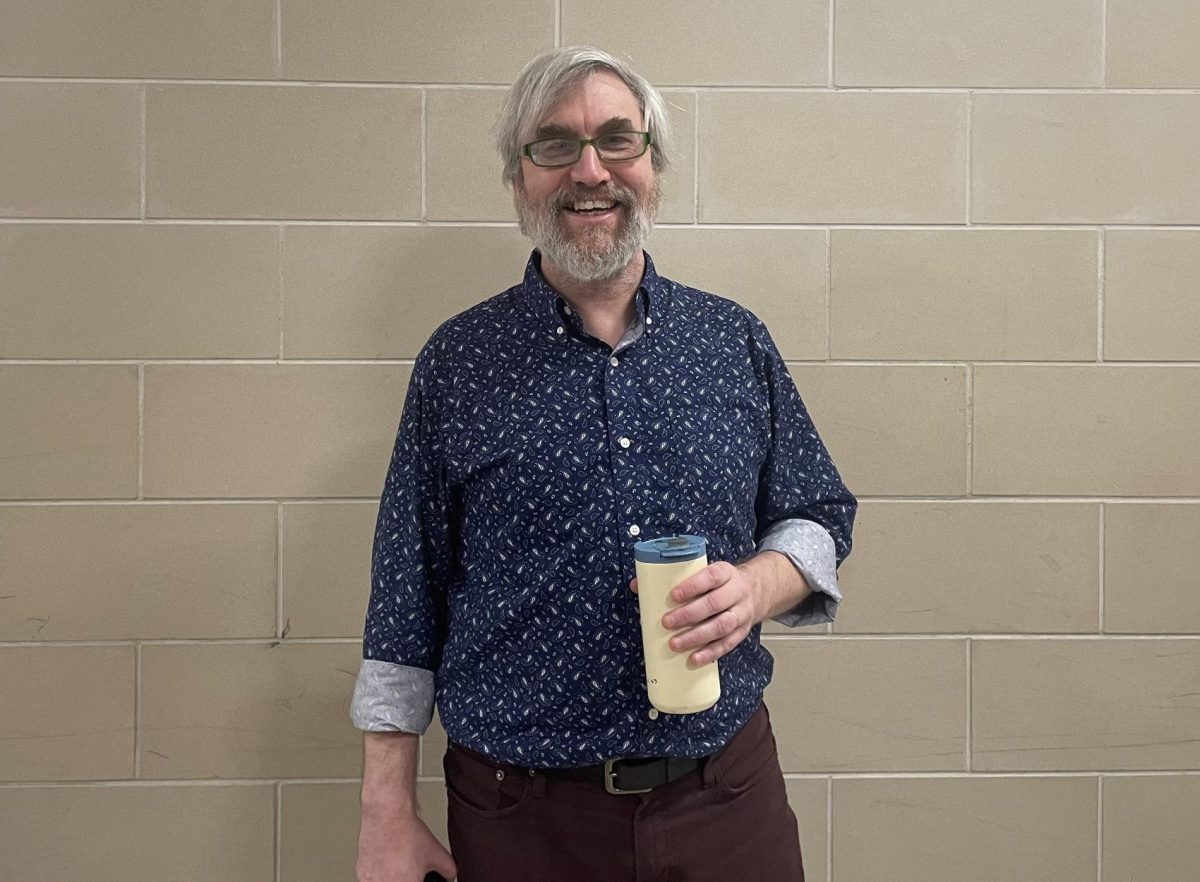

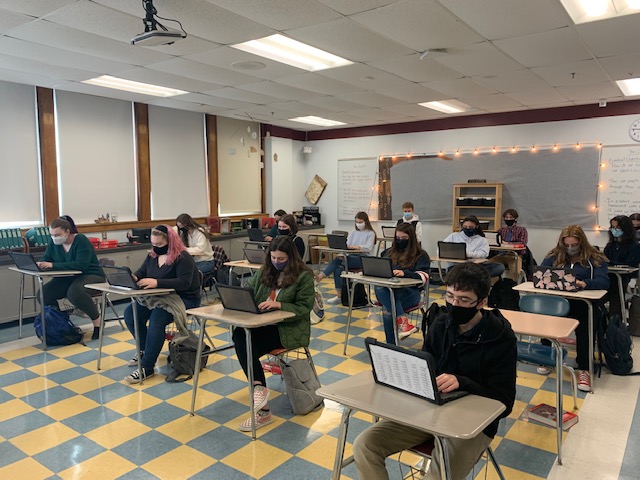

Students attend English class. This is school now.

Over two months into the new school year, and we’ve finally started to establish a normal rhythm. Half days are becoming routine. Remote class is familiar, if not preferable. We’ve also done a great job curbing COVID-19 transmission, with no district cases resulting in the spread of the virus. With that in mind, I’d like to discuss an inconsistency which I’ve noticed at Gloucester High School.

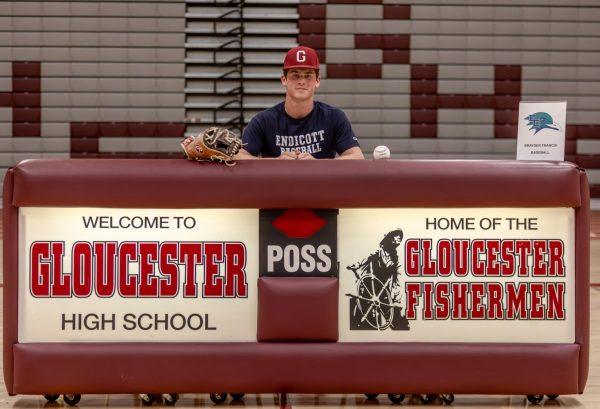

This fall, most sports teams were granted permission to participate in modified seasons. Practices began before students were even in the building. Meanwhile, students remain unable to turn around in their desks during class discussions, or work in small groups.

COVID protocols require students to sit in rows of desks facing forward at all times. Before the pandemic, desk pairs, pods, or circles were commonly used for discussion and collaboration. But if we are allowed to play sports, there should be more flexibility in the classroom.

There is no seating chart on the soccer field; no definite way to determine who was near whom. Furthermore, it’s even harder to identify the duration for which two athletes were together than two students. And sports teams are not divided by cohort. It’s not as if transmission during athletics is exempted from the evaluation of in-school transmission. Why then, is the classroom held to a different standard?

Sports take place outside, unlike classes which operate in the building, and this is a main argument in defense of the current model. But as cold weather approaches, we’ll start to see competition move inside, with the commencement of basketball, hockey, and other winter sports. None of these seasons have yet been cancelled.

Does turning and talking at three feet of distance drastically increase the incidence of transmission? More so than playing field hockey? Would changing the seating arrangement, while documenting those in groups together, really be more dangerous than riding the bus to Salem or sitting on the bench with teammates when subbed out of play?

And if we feel safe doing one thing and not the other, perhaps we should ask why. The importance of students and teachers feeling safe cannot be overstated – especially since the sentiment of the community is so essential to the school’s ability to operate. But our concerns should be rational and evidenced, and our responses to these concerns should be consistent.

To be clear – I’m a proud GHS athlete who participated in soccer this fall, and I’ve seen first hand how diligent students and coaches are being about adhering to the guidelines. But the fact is that proceeding with sports is a risky business, regardless of MIAA COVID restrictions. Contact is difficult to avoid completely; social distancing impossible to maintain in all circumstances. It’s the truth, and it’s not a secret.

I’m not saying it is totally irresponsible to take this risk; after two months we haven’t seen major consequences, and it’s even possible that sports don’t play a role in facilitating transmission. The point is that if we opt to take that risk, we ought to be honest with ourselves about what we’re doing and apply that same standard of safety with constancy.

The location of a school-sanctioned activity, whether it be soccer practice or English class, should not dictate the rigor of the safety precautions associated with it.

Now you might be asking yourself, why does it matter whether not students can change desks? Having students sit in rows forward-facing might not seem like too much of a sacrifice, but it really can’t be overstated how acutely rules like these have changed the classroom experience.

The ability to work in partnerships and small groups provides a break from lecture-based lessons, allowing kids to play a more active role in their studies, and take risks they might be unwilling to when working with the whole class. It also generates opportunities for assignments that are creative, collaborative, or research-based – all qualities that tend to motivate students.

Sitting in a circle or desk pod also makes education much more personal. It’s hard to have a serious discussion when three quarters of the people you’re talking to are behind you. It’s hard to read the room when you’re staring at the backs of your classmates’ heads. Social cues are critical to productive conversations; removing them creates conflicts and disrupts the natural flow.

And in general, flexibility allows teachers to design the spaces they feel are most conducive to their subject and style. Different classes require different activities, and the way a room is set up reflects the way it functions. Sometimes rows work perfectly – like during independent work and assessments – and other times they don’t. Unyielding rigidity can be detrimental to a classroom environment. After all, learning is a dynamic process! Creativity is not linear, and neither is growth.

Consider it this way: COVID-19 public policy is a gambling game. It’s the process of applying health data and cost-benefit analysis to organize risk in a way that’s likely to be least harmful to the most people. Though it’s impossible to completely eliminate the incidence of transmission without terminating all in-person interaction, it is reasonable to assume that we can, through precautionary measures, reduce it.

Playing the game is a matter of calculating which industries and institutions are most justified in perpetuating risk. Schools have been deemed imperative to societal function so they’ve been allowed to open, despite the liability of hosting lots of people in a shared space. Danger is inevitable if we plan to reopen, so it’s logical that we should try to control it.

The point is, priority matters. The way policy makers and administrators organize their ‘gambling chips’ reflects what they consider most fundamental to the function of our communities.

When we concentrate our risk in sports rather than school, we’re making a statement. We’re placing athletics above education, by our actions if not by our rhetoric.

Over the past few months, the importance of having schools open has led to more than one double standard. Six feet turned into three feet when it came to establishing a safe distance. The number of people you could gather with at school became larger than that of private gatherings. Mask breaks are allowed in schools but not the grocery store. And yes – sometimes rules must be bent. Theory can’t always translate to reality. Compromises must be made. But we really have to try.

The bottom line: COVID-19 safety is all or nothing. If we hold different situations to different levels of precaution, we’ve illusioned ourselves. We’re really only as careful as our most risky endeavor.

We are facing a choice. Either concede that both sports and seat-switching are both risks worth taking, or err on the side of caution and denounce both practices. Any other course of action is illogical.

Mila Barry is in her fourth year at Gloucester High School, and her third year on the Gillnetter staff. Outside of writing for the newspaper, she’s...

Mila Barry is in her fourth year at Gloucester High School, and her third year on the Gillnetter staff. Outside of writing for the newspaper, she’s...

Kaylee Curcuru • Nov 20, 2020 at 12:51 pm

This article makes a lot of sense and I understand what she is saying. She is contrasting between the precautions we take during sports and in school. Most sports take place outside so there is more independence and we can move freely. When in school the rules we follow are more strict. The seats are in rows and we have to follow the arrows to go a certain way. This can sometimes get a little annoying but it keeps us safe so it is necessary. Personally I think the way things are right now are doable and is the best solution. All in all these are difficult and sensitive times and we all need to do our best to keep each other safe.

chase • Nov 20, 2020 at 10:00 am

I understand what you are saying it would be nice to work in groups again, but if its one or the other im choosing sports. I agree there is not much of a difference but in sports you are moving you arent repetitively standing or sitting next to the same person for a long period of time.