The Gloucestermen: a preserved people in the face of change

A diorama of the physical change in Gloucester with quotes that define what the essence of a “Gloucesterman” is. Made by Soo Ae Ono, Vidriana Catanzaro, and Caroline Enos

June 14, 2017

For those who have lived in or visited Gloucester, it is clear that the physical presence of the city has evolved through the years. Schools have come and gone, neighborhoods torn down and replaced by businesses. Most notably, the economic staple of this city is transitioning from its 400-year old fishing industry to the influx of tourists each summer.

“In my eyes, Gloucester is a tourist place, not the city of the past when the fishing industry was strong and provided many jobs for people,” said John R. Speropoulos, who grew up in Gloucester and graduated from GHS in 1969.

With NOAA reporting a 75 percent decline in North Atlantic cod stocks over the past decade- as well as changing climates and habitats that are forcing out healthy populations of species from the region- and implementing heavier fishing regulations, tourism has helped pick up the slack in terms of Gloucester’s economic sustainability.

“The loss of the oldest fishing community ambience concerns me, as its history has been made by ‘those who have gone down at sea,’” said Esther Robbins, who lives in Vermont and visits Gloucester frequently.

The cultural shift between the core of what the city once was and the core of what the city is becoming has left a very important question prodding at Gloucester, and every other community that is deeply rooted in its history.

Even though a place changes physically, does the essence of its locals change as well?

Charles Olson: How has Gloucester really changed?

Gloucester poet Charles Olson’s perception of Gloucester’s culture is a key indicator in the answer to this. Olson, who once found solace in the community before urban renewal and the decline of the fishing industry, was deeply disturbed by the physical changes seen in Gloucester’s downtown and historic districts.

“Bemoan the easiness that smashes anything,” wrote Olson in his 1965 “A Scream to the Editor.” “Stop this renewing without reviewing… I’m sick of caring, sick of watching… I hate those who take away and do not have as good to offer.”

Like many of his contemporaries, Olson struggled with the changes that came with the sudden demolitions of old neighborhoods and buildings.

“For anyone who grew up here, to see the difference in the 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s; to see the changes, which in some ways were incremental, but which as you got closer to the 60s were extremely dramatic, it can be said that it had been a loss of character, there had been a loss of original beauty,” said local writer Peter Anastas.

Olson was right in that some of the change was an unnecessary loss of history and culture. He was right in that the past should be somewhat preserved in a place that continues to be so dependent on it, both industry and culture wise.

But like many other Gloucestermen, Olson’s drive to protect his ideal life proves two important points.

One: Olson’s stubborn disposition and impassioned desire to preserve his perception defines a true Gloucesterman.

Two: Physical change does not bring imminent doom for what was once constant. It is the people who allow the beauty and essence of a place to continue to live, even if in moderation.

The shifts in being a Gloucesterman

With a higher regard for education, concerning amounts of drug use, and rising property rates and living costs, Gloucester has continued to change in the time since urban renewal began.

“Heroin here was bad when I was a kid, it got better for a while, and then it got bad again,” said Katie Rabbitt, who lived in Gloucester until she was 12 and again for a brief time in her 20s. “There used to be a way for people to make money through hard work, now it doesn’t seem like it. Boys were raised to fish, girls were raised to be wives. Now it’s more like the rest of the state and learning is more important.”

About twenty locals, new residents, and visitors of all major ethnicities and backgrounds commonly found in Gloucester were interviewed for this article through a series of questions asked in Gloucester Facebook groups or in person. Another dozen first hand sources detailing what it is like experiencing Gloucester were also referenced.

In trends that can be seen in other communities throughout the country, many responses noted that Gloucester has lost some of its neighborly feel and downtown charm.

“People used to do their shopping downtown. Neighbors used to be a lot more friendly and talk to each other every day,” said Millie Sanborn, a Gloucester resident since her birth in 1924. “You really don’t see that anymore.”

When asked how Gloucester has changed physically, most responses acknowledged the effects of urban renewal and the decline in the fishing industry, as well as the new hotel and other tourist-geared businesses that have emerged in recent years. To many, the definition of a Gloucester person, or a “Gloucesterman,” was reflective of this.

“Most Gloucester people are self made, not followers,” said 65 year resident Hugh Parkhurst. “The decline of fishing means that once hard work could provide. Now to provide requires independent knowledge or skills.”

What a Gloucesterman really is

When asked how to describe a Gloucesterman, many responses were rooted in the fishing industry’s influence on the community.

“The fishermen call themselves Gloucestermen not because they provide their hometown with a lot fish. They call themselves this because they don’t know the meaning of ‘fear,’” said student Kristina Lazutkina, who moved from Russia to Florida, in an essay analyzing “The Perfect Storm” for one of her classes.

“They are men who never give up. They are men who have a goal and do everything to reach it,” said Lazutkina. “The Gloucesterman is adventurous, brave, and warm-hearted. The Gloucesterman always supports and protects their fellow crewmembers.”

Several of those interviewed stressed that the locals here never change.

“People in Gloucester seem to never change as long as you don’t change yourself,” said 20 year old David Tucker, who has lived in Gloucester for 18 years. “You’ll always have the random nice people who waved to you even though you don’t know them, as well as the nice man who holds the door open for you even though you’re 20 feet away.”

According to Angela Taoromina, “Gloucester people are a different kind of people. You can’t explain them, you need to experience them.”

But for most of those who answered, a Gloucesterman is someone who is strong willed, accepting, and willing to lend a hand to anyone in need.

“Gloucester people are tough and innovative and unlike any other people in the world,” said 18 year old Jacob Belcher, whose family has been here for several generations. “They can be rough around the edges, but at the same time they have really huge hearts and care about where they live and are always looking for ways to benefit our environment and community.”

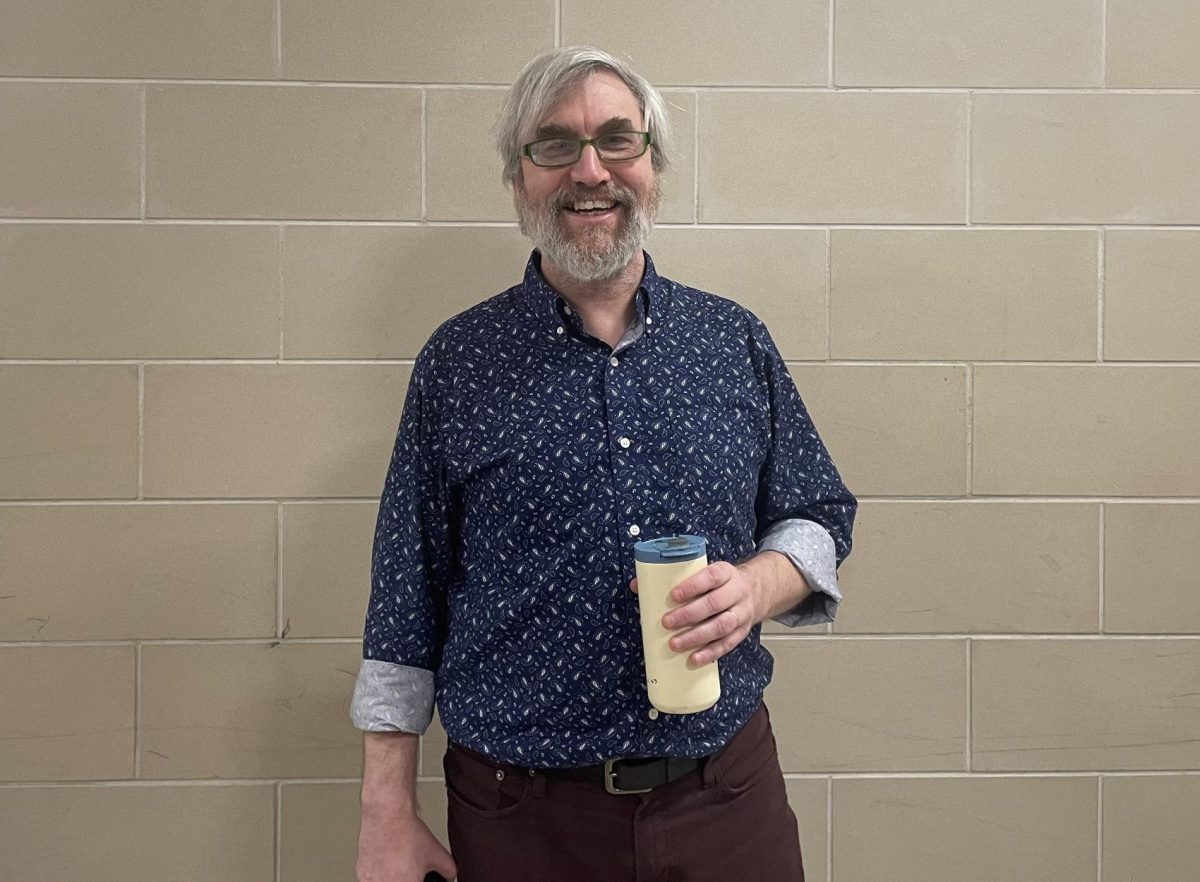

Many identified the Italian and Portuguese communities as major parts of the overall culture of Gloucester. Scott Enos, whose family has been in Gloucester since the 1600s, said it is the “family oriented and proud nature” of these cultures that have helped shape the definition of a Gloucesterman. He also noted that different social classes and communities have become more prominent in the city’s cultural landscape.

“In some ways, Gloucester is really ‘Two Gloucesters.’ The rich Eastern Point, Annisquam residents, who do contribute to society through their financial donations to the city, and then the ‘working-class’ Gloucester, those who work in the declining fishing industry or such places as Gorton’s and Varian,” said Enos. “Even though in recent years different ethnicities have come to Gloucester, I believe that they are being welcomed and incorporated into the general population.”

How tolerant is a Gloucesterman?

GHS juniors Yanna and Lizbeth Peña-Ortiz moved to Gloucester four years ago, and originally hail from Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico.

“I feel like [Gloucester] is changing after being here for four years,” said Yanna. “I think [Gloucester people] are becoming more opened minded. They’re letting new things come to Gloucester and are trying new stuff, perhaps Italians learning Portuguese or even Spanish. There is a minority of Spanish people here, and I feel like after a while more Spanish people will come and be comfortable here.”

Some believe that Gloucester, like many other communities, still has some ways to go in terms of being more open and accepting towards those from “over the bridge.”

“Everyone has connections here, and to me, I believe the people aren’t as open to diversity as they could be,” said Lizbeth. “They have standards.”

But for Alexander Oaks, a sophomore at GHS who spent most of his life in New York City, being gay in this community is much more accepted than in other places.

“Most people here seem to be accepting [of the LGBTQ community], and if they’re not, then they’re quiet about it.” said Oaks. “I haven’t had a lot of problems here.”

Gloucester people have been praised and cursed for having an “island mentality,” or often trying to isolate themselves from the rest of the world. Oftentimes, this comes with the stereotype that Gloucester is inclusive only to those already in the community.

Julia Butler, a graduate of the GHS class of 2017, and lifetime resident Jane Fosberry Enos claim that this is not true.

“None of my family lives here and my parents moved here, so I’m a first generation Gloucesterite,” said Butler. “I feel that Gloucester is a welcoming community to newcomers and people outside the tight-knit extended family dynamic.”

“When I think of Gloucester people, I think of tolerance,” said Enos. “For the most part, while they may speak their mind and sometimes lack tact, they are very accepting of other people. We accept people’s flaws and help however we can.”

This tolerance was seen in the comments section of The Gillnetter’s article “Executive order hits home for Gloucester,” where one of the many comments that supported a young Syrian refugee in Gloucester specifically outlined what place he and his family now have in the community.

“We are one big family and share a lot of experiences, good and bad and take care and watch out for each other, as we will you and your family,” wrote Salvatore Cuomo. “I wish you well here in America and hope your dreams of a better life are fulfilled and that we in Gloucester will be part of it.”

While there is room for improvement, Gloucester is far more open minded towards other cultures than it may appear to be. But when the topic of tolerance shifts to physical change in the city, and when or if it is necessary, things get a bit more complicated.

Change: the best friend and worst enemy of a Gloucesterman

For Charles Olson, the fishing community, and many others, the change that came with urban renewal and the decline in the fishing industry threatened a sacred, traditional way of life in Gloucester.

“[Gloucester people] are pretty set in their ways. The older generations don’t like change,” said Cindi Williams, GHS class of 1969 alumni and lifelong Gloucester resident. “Traditions matter, as does family. But there is still a lot of clinging to the past, especially surrounding the fishing industry.”

The building of an upscale hotel, the drastic makeover of Main Street into a tourist-centric place, and a slew of other infrastructure changes has altered the picture many Gloucestermen still have of the city.

“[Charles Olson] had a real good feeling of what Gloucester was all about, and I think that’s what disturbed him, and that he saw that that was disappearing,” said one man interviewed in Henry Ferrini’s “Polis Is This,” a documentary about Olson. “But everything changes.”

According to Jane Fosberry Enos, Gloucester people have proven to tolerate those around them.

“One of the only things they do not tolerate well is change,” said Enos. “They resist things that might even be good for the city, like a new hotel replacing an empty, broken-down fish plant; or a new shopping plaza that finally brings an affordable Market Basket and Marshalls to Gloucester.

“But that resistance to change also protects architecture and landmarks, keeping history alive,” continued Enos. “It’s never pretty when someone starts talking change, and it takes a lot of persistence to make change happen. And some will never admit that the change turned out to be for the best.”

Some are encouraged by the changes they see in Gloucester.

“Down the boulevard, they planted new flowers and keep it clean. It’s really beautiful,” said Yanna Peña-Ortiz. “I like that they keep planting new flowers instead of letting them die.”

There is no obvious answer for what change will bring for Gloucester. But as the people of every living generation in Gloucester have shown, the essence of what it means to be a Gloucesterman seems to have remained the same throughout history.

“A true Gloucester person- and that could still be someone who hasn’t lived here their whole life- is someone who is proud of the beauty of this town, who appreciates the scenery, the fishing industry, and the history,” said lifetime resident Leigh Ann. “Someone who doesn’t get annoyed at tourists but rather talks to them and gives them advice on where to go and what to see.”

The Gloucesterman still lives on even with urban renewal and the decline of the fishing industry. The Gloucesterman is still passionate for his home, as the prideful accounts of what it means to live here show. He is still stubborn in his convictions, but not necessarily in his perception of others. He is still a product of the past, even with the discrepancies of the present.

As Olson once said, “The local is not a place but a place in a given man. What part of it he has been compelled or else brought by love to give witness to in his own mind, and that is the form, that is the whole thing as whole as it can get.”

Vidriana Catanzaro and Soo Ae Ono contributed to the research and interview process of this article. Some responses have been edited for length and clarity.

lyn • Feb 21, 2021 at 2:50 am

Great article.

I got interested when I watched Perfect Storm

Ann Sheridan • Jun 16, 2017 at 9:58 pm

It was a pleasure to read this creative article about the history and charm of Gloucester as written by the talented students of Gloucester high school. Surely this article contributes to the history of this remarkable city and its people.

Alyson Saben • Jun 14, 2017 at 8:46 pm

What a fantastic article. Kudos to the talented students who wrote it.

Melanie MacDonald • Jun 14, 2017 at 4:20 pm

This is such a well written article!