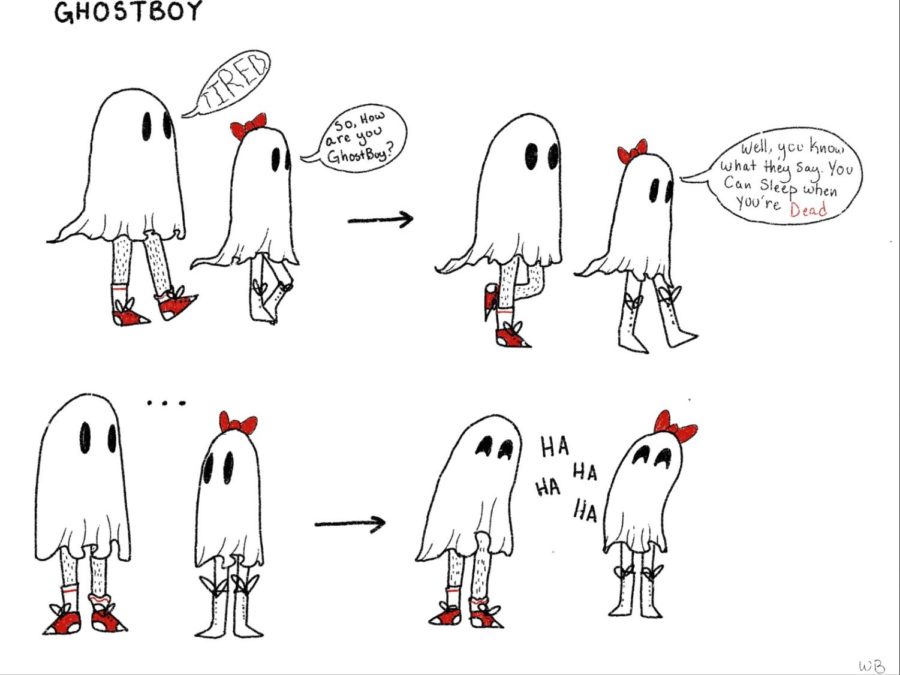

There was once a time when the first years of one’s life were defined by crayons, cardboard, sidewalk chalk, and dress up. Classrooms were filled with creations born from imagination, boredom, and trial and error.

These moments are now being replaced by screens.

In more and more classrooms, the sounds of creativity and learning have faded into the tapping of keyboards. Today’s students are growing up in a world saturated with technology. Devices are present from the moment we wake up to the moment we fall asleep. This often shapes the way students learn, interact, and create.

While technology has undoubtedly opened up possibilities that were impossible before, there is a growing concern shared by parents, scientists, and educators: technology may be eroding the essential form of growth called creativity.

This is a warning rooted in observation, experience, and research. Teachers at every level of education notice changes, not just in attention spans or handwriting, but in how willing students are to imagine, to take risks, and to think for themselves.

This creativity crisis begins at the earliest levels of education.

Third grade used to be full of paper castles, puppet shows, and creative stories spun out of only the brains of young kids. But now, if you walk into some classrooms during free choice time, you might hear only the tapping of keyboards and the occasional sound effect from a math game on their Chromebooks.

In a thoughtful interview, a local elementary school teacher reflected on the creativity shift that she has seen in her students. It’s not just nostalgia, but instead a growing change.

“It’s really hard for students to think on their own,” Abigail Andrew, a third-grade teacher at East Veterans Elementary School said.

Andrew encourages flexibility in her math lessons, asking open-ended questions and pushing students to write their own word problems. But still, she notices something missing: imagination.

“Sometimes I don’t let the students use their Chromebooks during free choice time,” she said. “And those who use a lot of technology are at a loss for what to do instead…they just wander around the classroom or sit and do nothing.”

The description is bleak; however, it is echoed by educators throughout the country. Students raised on screens often lack the resilience to invent, struggle through unstructured moments, or to explore ideas without prompts or dopamine from a device.

What’s especially striking is how early these patterns form.

“I feel like I can tell when parents restrict screen time at home,” she said. “These students often have better attention spans, more motivation to learn, more strategies for interacting with peers, and more imagination when there is an absence of direction.”

The difference is direct: children who have had time to be bored, to play outside, use their imaginations with siblings or friends, or build pillow forts, often show up to school with stronger creativity.

The damage isn’t just mental or emotional. It’s physical too.

“Handwriting has become atrocious,” she added.

With more typing and less fine motor practice, even basic skills like letter formation have deteriorated. And the fatigue that comes from late-night screen exposure.

“A lot of them come in and fall asleep or complain that they were up too late playing games or watching YouTube.”

However, Andrew doesn’t vilify technology entirely. She embraces some digital tools in the classroom. Her students create Google Slides presentations for Social Studies and get to choose fonts, colors, and images. “There’s a rubric,” she said, “but I let them be creative.”

But the creeping question remains: are these small doses of creativity enough to outweigh the passivity that screens encourage?

She wrestles with the same paradox many educators face. “Do we adapt to this new addiction to technology and have students use it more often? Will they be more engaged?” She doesn’t answer that question directly, perhaps because there is no perfect answer, but she continues to search for a middle ground. One where creativity and technology don’t compete but coexist. One where kids still know how to build something out of nothing.

The warning signs aren’t just coming from classrooms; they’re backed up by neuroscience, psychology, and education research.

In the book Mind Change, Susan Greenfield compares the effects of digital technology on the brain to the way that climate change impacts the planet: slow, complex, and devastating if unmonitored. She warns that too much screen time during developmental years can rewire the brain circuits associated with focus, empathy, and imagination.

When young minds spend more time reacting to stimuli than generating their own thoughts, it becomes harder to think deeply, critically, or creatively.

Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows makes a similar case. He argues that the internet has literally reshaped the way that we think, prioritizing speed, multitasking, and surface-level engagement over deep, sustained thought.

“What the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation,” Carr writes. When our minds are constantly pulled towards distractions: alerts, tabs, and notifications, the mental conditions required for creativity begin to fade.

These concerns are echoed in real-world studies. The Growing Up Digital (GUD) Project, a research initiative being performed in Canada, found that excessive screen time correlates with a drop in key cognitive skills, including memory, focus, and executive functioning. All of which are essential for imaginative problem-solving and creativity. Students who reported higher screen use were more likely to struggle with sustained attention and to feel disengaged from learning tasks that did not offer immediate rewards.

A 2022 Harvard study on the impact of screen time on children’s brains highlights that too much digital engagement in early childhood is associated with reduced white matter development. This is the part of the brain involved in language, reading, and self-regulation. In short, screens may be doing more than just distracting kids from play. They might be physically altering the way kids think and learn.

This article states that today’s youth are “lacking the deep REM sleep essential for processing and storing information from that day into memory.”

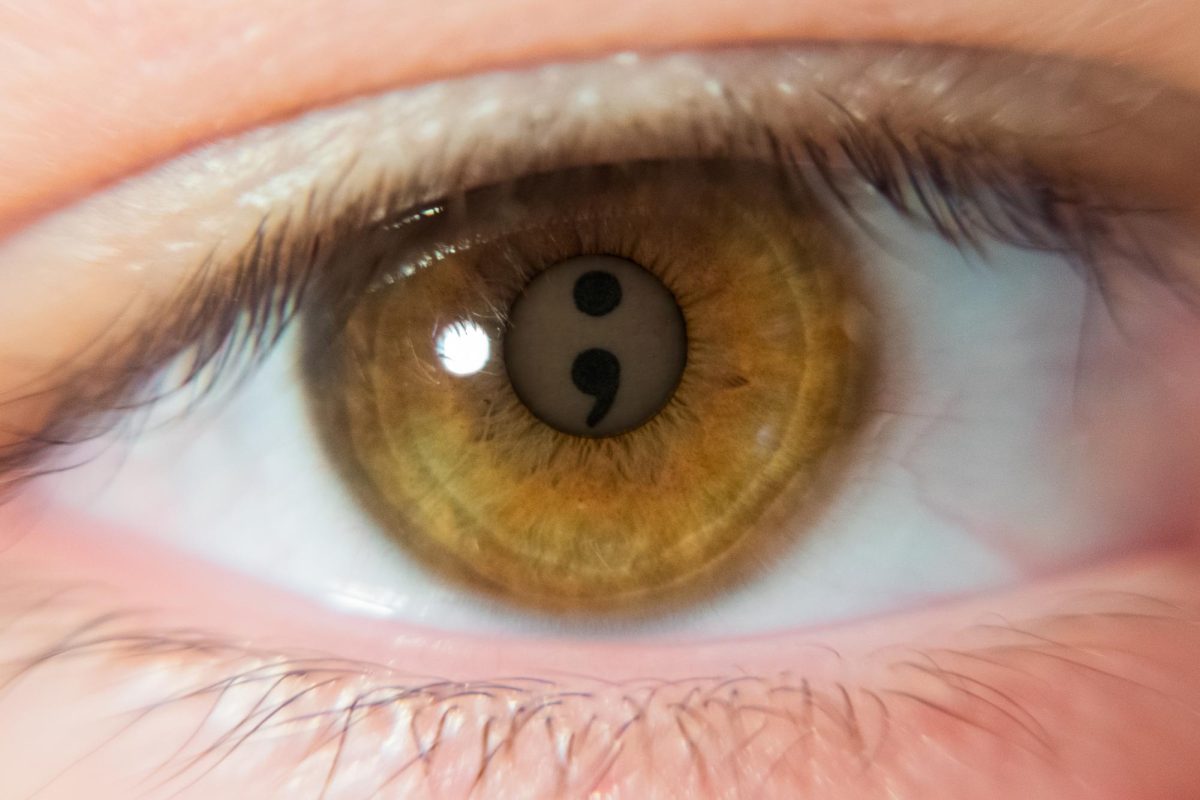

And now, with artificial intelligence entering the picture, even creativity itself is being outsourced. Students can ask AI to write stories, generate art, solve problems, write music, and it often does a decent job at doing so. But when imagination becomes a button we press instead of an everyday muscle used, something irreplaceable is lost.

Adam Dameri, a sophomore student at MassArt majoring in art and photography, described his relationship with technology as two-sided.

“I think modern technology can enhance creativity, but at the same time, we are seeing a damper put on individual ideas because of AI development,” Dameri said.

This creativity crisis isn’t about banning technology. It’s about asking what we want from students, and from ourselves. Do we want fast results or deeper thinking? More answers, or more originality? The tools we give to children today will shape the important minds of the future. If those tools are only screens, we risk raising a working generation that can click, tap, and scroll, but not imagine.

If creativity is the lifeblood of progress, the spark that drives invention, storytelling, empathy, and expression, then we should be worried.

Is society at a creativity deficit?

Educators throughout Gloucester High School are already expressing their concerns.

“I think our world is so image-heavy,” said Mrs. Cerruti, an art teacher at GHS, “that trying to come up with an original thought is a lot harder for young people… very rarely do people come up with their own artistic ideas because now you can Google something and create art from someone else’s ideas with an easy way out.”

In a world where inspiration is endless and immediate, imagination is increasingly outsourced. Creativity, once messy and difficult, has been flattened into a copy and paste exercise.

The concern isn’t just in the arts, but for other academic disciplines as well. “AI is superseding ideas,” GHS English Teacher Michael Telles said. He can often sense when a piece is written by a machine (clean, competent, but with a lack of originality) rather than coming from a true personal thought. “I think from a school perspective, creativity is being squashed.”

However, not every teacher sees a one-sided crisis. Gloucester High School history and modern government teacher Alyssa D’Antonio sees both sides of this question. “We have a wealth of creativity available to us,” D’Antonio said. “But we are limiting ourselves in the ways in which we create.” She highlights her frustration with modern media: Remakes, recycled intellectual properties, and AI-generated stories reflect a larger issue: convenience has replaced struggle. “People aren’t letting themselves find tension in their ideas,” she said. “We’re robbing ourselves of collaboration and connection, which affects us creatively.”

In other words, it’s not that people aren’t creative; it’s that many are no longer practicing the process of creativity. Society is skipping the hard part. And yet, that hard part, the struggle to make something meaningful, is exactly what builds deeper thinking, confidence, and innovation.

Other educators point to the psychological cost of living in the digital age. “We’re bombarded with snippets of information and quick bites of things online,” Teresa Gallo, an Italian and Spanish teacher in the worldlanguage department said.

“Our minds are cluttered,” Gallo said, “We want immediate gratification and a final piece, which makes students turn to AI.”

She believes that this demand for speed and perfection has made it harder for students to be creative. Not because they don’t have the tools, but simply because they do not have the space to think.

Jessica Lichtenwald, a Biology and Life Science teacher in the science department, had a similar view, but much more blunt.

“Students cannot think for themselves anymore. Instead of writing their own lab reports or their own essays, they use AI,” she said. “What’s the point of doing labs if kids aren’t going to come to their own conclusions?”

What she’s implying is a large general concern: If students stop practicing creative thinking, will they eventually stop knowing how to do it at all?

When I asked students themselves what they do to be creative, the answers were sparse. Some mentioned theater, painting, or dance. The majority of others said simply “nothing.” These aren’t kids that you would call “lazy.” Many of them are hardworking, honor roll students. Unfortunately, even society’s top students and hard workers are caught in a system where output is valued over learning, and efficiency is valued over exploration.

To answer the question, yes. Society is in a creativity deficit. Not because humans are any less capable of thinking creatively, but instead, we are unwilling to make the time and space to do so.

Creativity requires more than a screen and a search bar. It requires boredom, struggle, curiosity, and collaboration. It requires asking questions that do not have a fast and easy answer. So, how do we accomplish growing back creativity in society as a whole?

We are living in a world where creativity is slowly being crowded out. However, this situation is not entirely irreversible. Creativity isn’t gone, it is waiting for society to make room for it again.

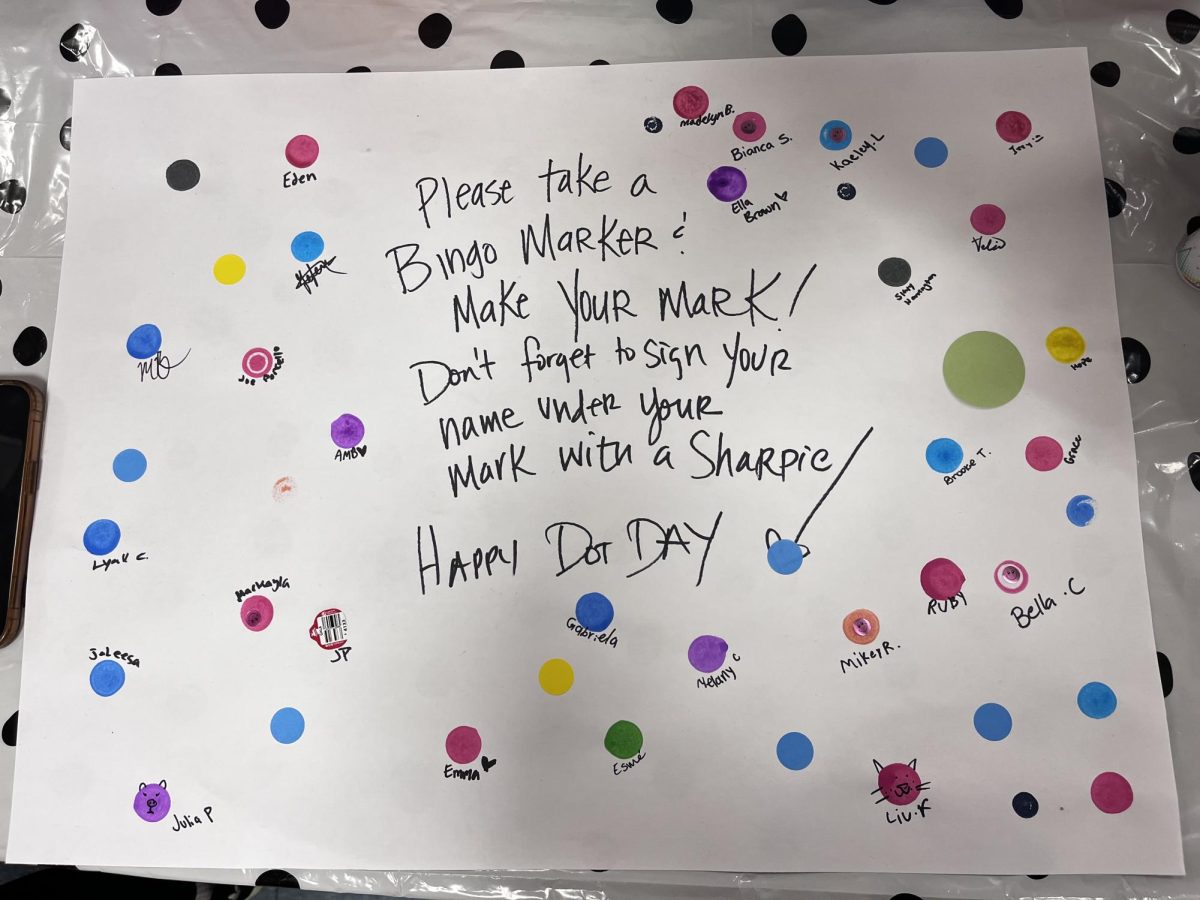

Boredom needs to be returned. Without boredom being part of childhood, many games, stories, and ideas that come from children would not have existed. When there is nothing to do, the mind is forced to create.

In many ways, boredom has been something to avoid. Every spare moment is now filled with entertainment, notifications, and distractions. Giving people the time and space to feel bored allows the building of imagination and the ability to come up with new ideas.We don’t need to eliminate technology, but we do need to protect time where screens are not an option. The quiet, peaceful times are where creativity thrives.

Creativity is also a skill to practice. It doesn’t just happen like magic; it develops with practice. Just like any other skill taught in school like reading, writing, or math.

Schools can build creativity into the learning process. Open-ended projects, design challenges, and problem-solving activities give learners a chance to explore and create solutions. Instead of always seeking the “right” answer, we can encourage students to experiment, revise, and expand their imaginations.

The key is to create environments where failure isn’t a fear, but rather the most important part of the necessary process. When people are willing to take risks, they are far more likely to push the boundaries of their creativity.

Technology is not the villain in this story. In fact, it can be a powerful tool when used with intention. The problem arises when technology does the imagining for us. Instant answers, pre-written essays, and AI-generated art remove the need to struggle through the creative process. Passive scrolling and nonstop media consumption drain the brain’s capacity to explore new ideas. But when students use technology to build; whether designing a game, editing a film, or recording music, it can be a modern canvas for creative thought. The solution isn’t to ban devices, but to re-frame how they are used. Active creation should be prioritized over passive consumption.

In a world that prioritizes speed, it’s easy to forget that creativity takes time.

When every task is timed, every assignment is rushed, and everything has a deadline, the space for deep thought disappears. Ideas don’t always thrive in chaos, they need time and quiet. This means intentionally creating moments to slow down. Time to revise, reflect, and wonder.

The biggest shift may need to happen outside the classroom. The problem is bigger than education; its everywhere.

When society values productivity over process, we teach learners to aim for the final product, not the thinking behind it. When perfection is emphasized, experimentation disintegrates. When success is measured in likes and views, depth suffers.

To restore creativity, we have to change what we reward. We have to celebrate the effort behind ideas, not just the final product. We have to remind society (including ourselves) that real innovation isn’t easy and instant.

Creativity is being neglected. It’s pushed aside by convenience and speed. However, fixing this does not mean abandoning modern life, but instead re-balancing it.

Students need time to be bored and think differently. People need to fail and be told to try again. There needs to be encouragement to build something from nothing but pure imagination.

If we fail to make space for creativity now, we risk raising a generation that can consume and copy, but not create.

![Grace Castellucci runs down a path during a race. [Courtesy photo by Manchester Essex Athletics]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_1581.jpeg)