“European American”: a case for a label

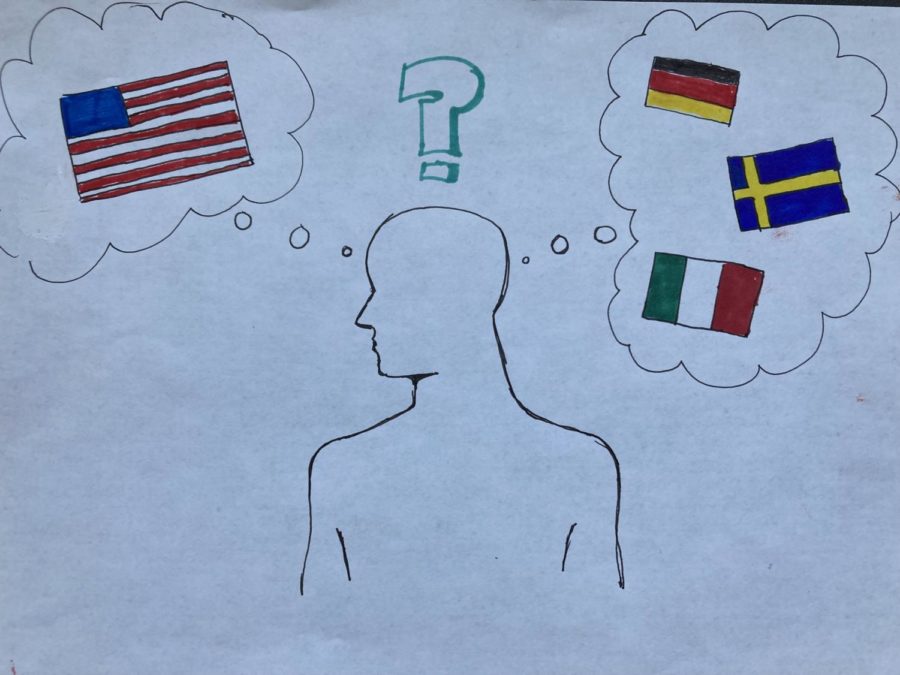

In America, the concepts of race and culture are simultaneously essential to our understanding of ourselves and others, and extremely difficult to define. Terminology is a minefield—trying to use correct language to define relatively arbitrary concepts is difficult, to say the least.

There is conflict within almost all racial communities about terminology, including those of primarily European descent. Racially, we refer to these people as white. Culturally, we typically use one of three classifications: white, Caucasian, or a specific ethnicity.

I propose an addition to our lexicon that is efficient, sensical, and more accurate to the experiences of many Americans: European American.

There has been much discussion within the black community in America surrounding this identifying language. “Black” and “African American” have been used interchangeably, but in modern times, there seems to be a distinction being made between “black,” “African,” and “African American.”

I consulted a few friends on the matter. Adama Sawi, a sophomore from Virginia, is of Sierra Leonean and Liberian descent.

“I consider myself black and African American, since I’m first generation,” Sawi said. “I am genetically and culturally black, because my parents, my grandparents, my uncles and aunts, all of them come from Africa. It’s not like my parents were born in America, it’s not like I’m completely African-American, I just happened to be born here.”

There are also those who choose to identify themselves as black, and not African American. Many descendants of enslaved people feel as though culturally, they have very little tie to Africa due to historical atrocities, and thus do not feel as aligned with “African American.”

Zoe Flint, a sophomore from California, is of both black and white descent. “Culturally, I probably feel the most attuned to “black,” because I have no connection to my African heritage. I don’t consider myself to be African at all, really. Maybe if I knew where in Africa I was from it would be different.”

The black community has been having this discussion for years. It seems time for white people to have it too. On some forms, surveys, and other instances where culture is deemed relevant, the box for people of European descent is sometimes listed as “Caucasian.” Technically speaking, that word refers to the peoples of the Caucasus Mountains, but it has come to refer to people who are, either racially or culturally, white.

But how did that term come to mean what it means? Unfortunately, its history is much darker than one may expect. 18th century racial pseudoscientists broke humanity down into three categories: Negroid, Mongoloid, and Caucasoid. They believed that humanity had originated from the Caucasus mountains, the alleged landing point of Noah’s Ark. Simply put, the Caucasoid race was thought to be the most directly descended from the original, most beautiful, and most “pure” people, and thus was treated as superior. The previously mentioned groupings were later adopted by Nazi eugenicists, and used to scientifically justify genocide and racism.

The irony is that today, by our current racial classifications, many people originating from the Caucasus mountains—the real Caucasians—would not be considered white in the US. Made up of the Greater and Lesser Caucasus ranges, the mountains stretch through regions of Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, etc. Many indigenous groups inhabit this region, and from an American perspective, several of these indigenous groups appear racially Middle Eastern or Asian, and definitively not white.

So it seems that “Caucasian” works neither as a racial label nor a cultural one. How does “white” hold up?

In my time on the internet, and in living in a community with a large Italian population, I’ve come across a gripe with the term “white”: “I’m not white, I’m Italian.” Though that is a specific example, similar logic can be applied to other European ethnicities.

That complaint is often written off as a racist attempt to dodge one’s own white privilege, and in many cases, that criticism rings true. But for some, that complaint may come from a place of feeling misrepresented – for an Italian immigrant, or someone who is first-generation, “white” doesn’t truly capture that person’s range of experiences in this country. “White” is an efficient and often important way to categorize race, but in terms of ethnicity, its vagueness may leave some people feeling misunderstood.

These conclusions bring us to my proposition: the use of European American as a cultural label.

We use labels like African American to describe American people with ties to Africa. So, after looking at the deep, inherent flaws and inefficiencies in our current language, what stands in the way of “European American”?

There are many beauties of “European American.” One, it is broad enough to encompass a wide range of experiences—those who have cultural ties to Europe—while remaining specific enough to be descriptive. Two, it is not inherently tied to race; any of European descent currently residing in the United States is free to use it. It is purely a cultural descriptor. And three, it lacks the complicated history and connotation of much of our current language.

Of course, attempting to create a perfect classification for a social construct is impossible. There is no one-size-fits-all term to encompass the broad range of human experiences, histories, and identities in regard to culture, which itself is incredibly complicated.

For instance, my maternal grandfather was a Slovakian-Argentine immigrant who came to the United States as an adult. Though he was born in Slovakia, he immigrated to Argentina as a young boy to escape World War II and lived there for his formative years.

Racially, he was pretty much as white as it gets. But culturally, he could’ve been well within his right to identify as Latino. Culturally speaking, he was as much, or more, Argentine as he was Slovak.

So where do we put him? Is he European American? You could say that, but that would partially disregard his experiences as an Argentine who came to America speaking Spanish. Is he Latino? Well, his first language was Slovak, and he was an immigrant to Argentina, no matter how young he was. Is he the broad, less specific “white”?

These are all valid questions, and certainly ones worth addressing. It is also fair to question why we even need such hyper-specific, tailored language. Some people in my life have asked me: wouldn’t it be better if we stopped putting ourselves in all these little boxes? Can’t we all just be “people”?

To me, that idea has the potential to be lovely. The idea of getting rid of all these boxes and everyone just being a person sounds more efficient and less stressful, certainly. But the point is, whether or not you think the boxes should be there, they are.

The concepts of race and ethnicity are self-perpetuating. They matter because historically, they have mattered. Wars have been fought, genocides have been committed, worlds have shifted over ideas based not in biology but in the ways we perceive and label each other. Labels have been weaponized to mischaracterize, subjugate, and “other” for as long as they have existed.

So, accurate labels are important because these concepts, race and culture, aren’t going anywhere. We do not live in a colorblind world, where words have little impact and everyone is ascribed the single, tidy label of “person.” These things matter because as it stands now, this system of classification is in place, and we have to find a way to exist within it while it does.

There will never be a perfect system of racial and cultural classification. Those two concepts are both malleable and essential to our own understanding of ourselves and the world we live in together. All we can do is look for the best possible ways to try and understand ourselves, accurately and honestly.

Aurelia Harrison (they/them) is a senior and Editor in Chief for the Gillnetter. Their interests include writing, thinking about writing, music, and talking....

Ashley Gullett • Jun 20, 2023 at 12:31 pm

Excellent article, Aurelia. An interesting proposition for the very imperfect and ever-evolving system of labeling race and ethnicity.

Livia Uhrovcik • Apr 29, 2023 at 8:46 am

Great article, thank you! Well writen, good survey, you put in words my fellings about thoughts.

Linda Mccarriston • Apr 27, 2023 at 11:20 am

Great article, especially for a high school journalist. Good thinking and good writing. Thank you.