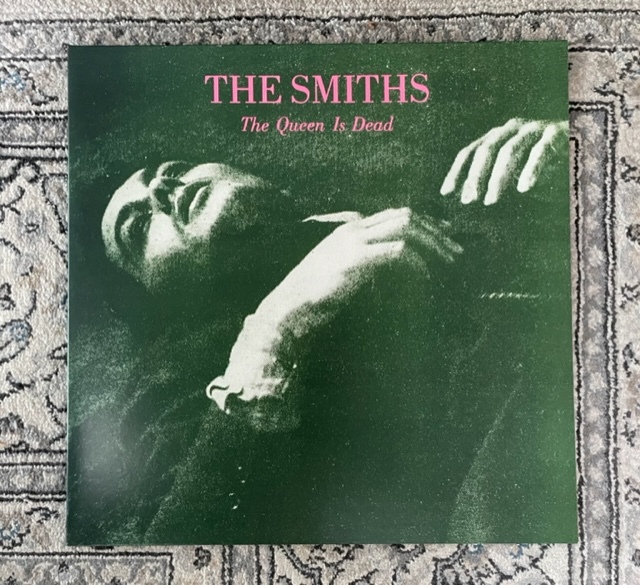

Old School Album Review: The Queen is Dead

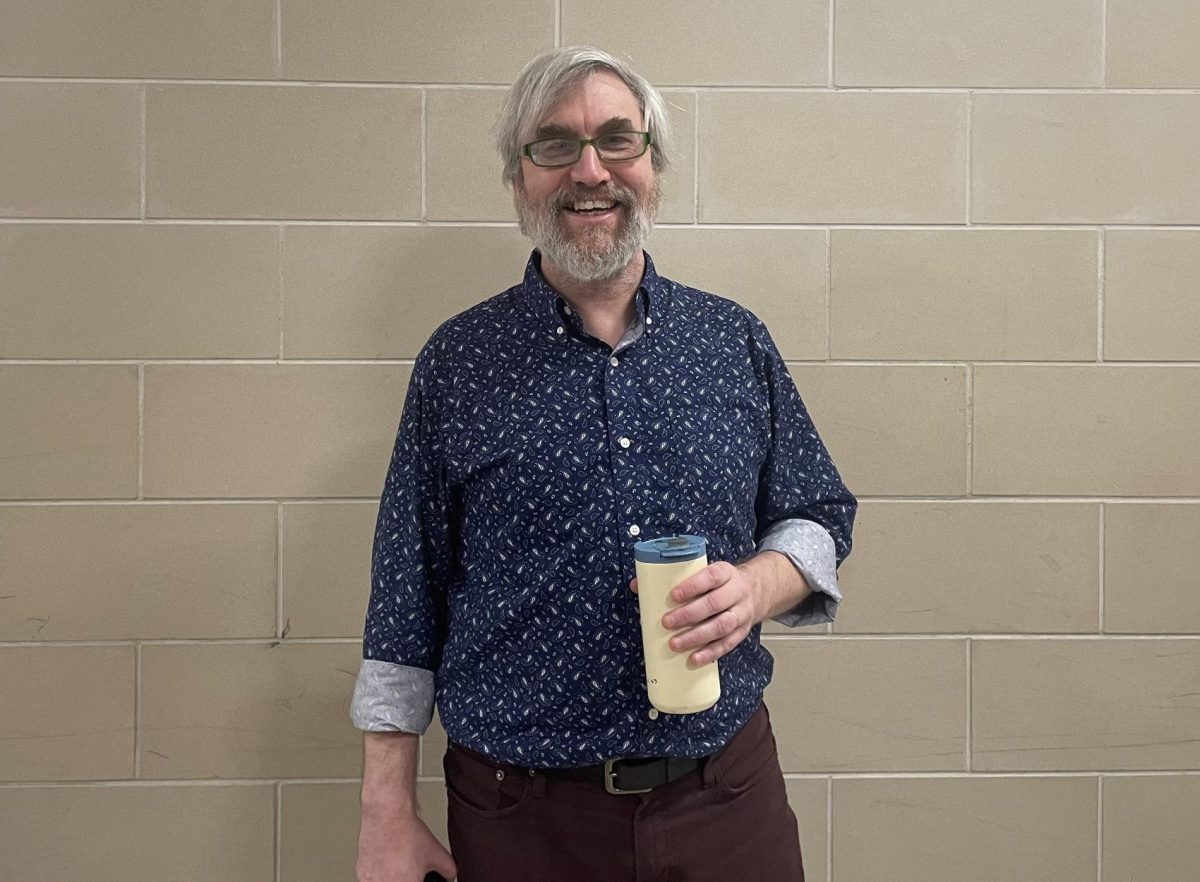

Photograph of a vinyl copy of The Queen is Dead album.

Despite its numerous drawbacks, the modern age of the internet has the benefit of allowing us music lovers unprecedented access to the music of decades past, or more colloquially, “oldies”.

For fans of the oldies seeking witty lyricism, expert instrumentals, and the nostalgia of UK post-punk, one need look no further than The Smiths’ 1986 album, “The Queen is Dead”.

Though the album title is perhaps slightly insensitive (but inarguably relevant) to our current situation, the record is absolutely one of the most iconic of its time. Produced and written by frontman Morissey and guitarist Johnny Marr, “The Queen is Dead” is a 10-track powerhouse, described best by journalist Gavin Edwards as “one of the funniest rock albums ever.” The album deals with everything spanning from loneliness, to love, to the monarchy, to breasts – and its instrumentation is less a background and more a partner to the lyrics, working in tandem (much like Marr and Morissey themselves).

In typical Smiths fashion, the album is not without its controversial takes. This is immediately apparent in the album’s opener and title track, “The Queen is Dead”. The song’s critical commentary on the English monarchy is startlingly relevant to modern day – the “Queen” the title refers to is the very Queen that passed away last September. The Smiths were not fans of the monarchy. The song’s second lyric refers to Elizabeth II as “Her very Lowness with her head in a sling” but, as fans know, hot takes are a staple of any good Smiths album. These lyrics are set to a fast-paced and experimental guitar line by Johnny Marr, a veritable guitar legend. The title track is what it seeks to be – an experimental and thought-provoking intro to the album.

The second track is a controversial one. Due to its sharp tone change from track 1, and its eccentric sound, fans tend to love it or hate it. Personally, I am of the “love it” persuasion. As it stands now, “Frankly, Mr. Shankly” is my favorite song of all time – I could very well spend the rest of this article talking about it, but in the interest of time, I’ll spare you. But whether you love it or incorrectly hate it, it’s a simple fact that “Frankly, Mr. Shankly” goes where few songs dare to go – that is, directly at the throat of the founder of the band’s record label. The Smiths belonged to Rough Trade Records for the better part of their career, and the song is an alleged shot at founder Geoff Travis and his “bloody awful poetry”, as the song puts it. Apart from the rumor, the song is a 2-minute gem of confessional lyrics from a working-class man to his boss, set to instrumentals that are beautiful to the track’s lovers and corny to those who aren’t listening hard enough.

Words cannot properly express the heart-wrenching gut punch that is track 3, “I Know It’s Over”. For the sake of my word count, all I will say is this: for moments of existentialism and feeling aimless, never a better soundtrack will you find. The following song, “Never Had No One Ever”, is a more standard, angsty track about loneliness – decidedly good, but not necessarily a standout on the album. However, it is followed by “Cemetry Gates”, an upbeat instrumental contrasted by morbid imagery of resting places and death.

The red, squiggly line that appears under “cemetry” as I type this is correct – Morrissey’s spelling of “cemetery” was less an artistic choice and more a careless typo. However, listeners may rest assured that the carelessness of the title does not translate into the song. The lyrics poke fun at accusations of plagiarism against the band – Oscar Wilde, who is often attributed the quote: “Talent borrow, genius steals”, is mentioned in the chorus as being “on my [Morrissey’s] side”. This could also be interpreted as a reference to Morrissey’s alleged homosexual tendencies, depending on whom you ask.

Track 6, “Bigmouth Strikes Again”, is one of the band’s most popular songs – and for good reason. Though the lyrics are fantastic (and slightly confusing), what really makes the song is Johnny Marr’s iconic guitar supported by the expert drumming of Mike Joyce and the steady bass of Andy Rourke. Along with the title track, “Bigmouth Strikes Again” is one of the more traditional rock-n-roll songs on the record, with an epically Smith-ian twist. I do not give out the title of “perfect song” lightly, but “Bigmouth Strikes Again” may well be deserving of it.

The popular track is immediately followed by another one of their hits, “The Boy With the Thorn in His Side”, which brings us into a lighter, catchier sound but whose lyrics are no less heartfelt. “The Boy With The Thorn in His Side” is likely best explained by Morrissey’s own words in an interview with Margi Clarke: “The thorn is the music industry and all these people who never believe what I said, tried to get rid of me… so I think [I’ve] reached the stage where if they don’t believe me now, will they ever believe me?” Morrissey quotes directly from the song here, and the lyrics are no less poignant when spoken.

Track 8, “Vicar in a Tutu” is the fourth Jonas brother of the album – it is the album’s least streamed song by a fair margin (but don’t feel too bad for it – 13 million streams is far from obscure). Despite its relative unpopularity, “Vicar in a Tutu” is just as strong as the rest of the album – its lyrics are a plea to society to allow people to pursue happiness according to their own inclinations: “A vicar in a tutu / he’s not strange / he just wants to live his life this way”. There is also a critical undertone in reference to the church’s money-hungry tendencies – this is still, of course, a Smiths song.

The album’s penultimate song, “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out”, is the band’s most popular song as of today (sitting at over 359 million streams on Spotify), due in large part to its popularity online, with the younger generation. It’s a love song – albeit a morbid one – and its bleeding-heart romanticism and violin-backed instrumentals make its inter-generational popularity only logical.

Rather than go for the old cliché of ending an album with a grand, dramatic ballad or a slow, misty-eyed piano jam, The Smiths go an entirely different route – bosoms. “Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others” is an eyebrow-raiser of a title (“girls” refers to exactly what you think it refers to), but at a slightly closer inspection, the song is a commentary on superficiality. The verses are brief complaints of society’s historic obsession with the female body, interrupted by absurd repetitions of, “some girls are bigger than others / some girls’ mothers are bigger than other girls’ mothers”. The song’s instrumentals bring the album back to a similar feel as the beginning, but calmer, simpler, an exit that puts you in the mood for more. Rather than ending abruptly, the song opts for a classic oldies fade-out, leaving the listener (and myself) ready to start the record all over again.

Aurelia Harrison (they/them) is a senior and Editor in Chief for the Gillnetter. Their interests include writing, thinking about writing, music, and talking....

Karen • Dec 13, 2022 at 10:23 pm

This article makes this oldie so happy.