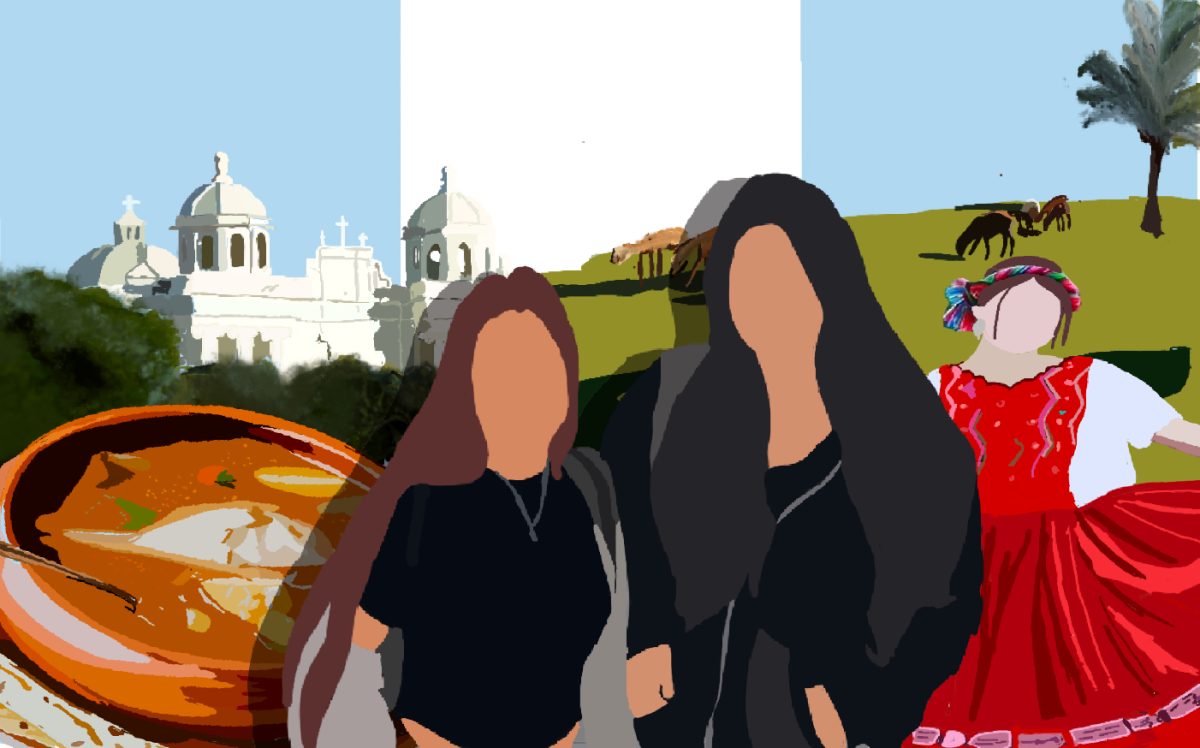

It’s easy for people to stereotype Gloucester High’s multilingual students with terms like “the Spanish girls.” For Jennyfer and Monica C., their dark eyes, brown skin, long black hair, and Hispanic friends might add to the misconception.

But these two cousins’ first language is not Spanish. Jennyfer and Monica grew up speaking Q’eqchi’, an ancient Mayan language that predates Spain’s colonization of the Americas in the 1400s.

The language, which is indigenous to Latin America, is spoken by around 1 million people in Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize. Besides Monica and Jennyfer, it is the first language of 9 students at Gloucester High School.

Q’eqchi’ sounds nothing like Spanish. If a classmate were to overhear the two girls’ banter in class, they might be surprised by the absence of clicky consonants and rolled rs. Instead, they’d hear a chorus of breathy noises, pronounced -ch sounds, and soft vowels — sounds that don’t exist in Spanish.

“It is very different to pronounce words in Q’eqchi’,” Jennyfer said in Spanish. “We write words with the c and h, but when you speak the words, it’s a lighter sound.”

It is true that Monica and Jennyfer are fluent in Spanish and have been speaking it for many years now. But to each other and their families, these two are much more comfortable communicating in the language they grew up with.

According to Jennyfer, when they were little, their parents mostly spoke Q’eqchi’ to them. The girls were introduced to Spanish when they started school and became fluent by the time they were eight years old.

Monica and Jennyfer grew up in the villages of Chisec and Sayaxché in central Guatemala. “Where we live is in the middle of nowhere,” Jennyfer said. “There are forests all around.”

Although Chisec and Sayaxché have predominantly indigenous populations, not everyone speaks Q’eqchi’.

“There are more groups that have other cultures than us and speak more languages, like the language Mam,” Jennyfer said. “There are like 20 or 21 indigenous groups.”

Indigenous traditions are different from mainstream Guatemalan culture in many ways. An important difference is the clothing they wear. When Jennyfer lived in Guatemala, she went to church four times a week. Each time, she wore her favorite piece of brightly colored, intricately woven, indigenous clothing. Sometimes she wore traditional dresses called trajes.

A popular piece of clothing worn in Jennyfer’s village was a woven skirt called a corte, which can be worn in many different ways.

“Some are wrapped, and some are loose,” Jennyfer said. “Some are short, but there are some that are long like the ones we wear.”

According to Jennyfer and Monica, there are some days when dressing traditionally isn’t unique to the Q’eqchi’ people. September 15th is Guatemalan Independence Day, which commemorates when many Central American countries gained independence from the Spanish in 1821. Independence Day celebrations showcase all aspects of Guatemalan culture, including the diverse heritage of the country’s indigenous populations.

The national holiday fosters a sense of unity and pride among all Guatemalan communities, and highlights their struggle towards sovereignty.

“Those who were born speaking Spanish hardly ever wear cortes,” Jennyfer said. “But we all celebrate September 15th. Then, those who speak Spanish wear the same style that we do, too.”

In 2023, Jennyfer and Monica left their lives in Guatemala behind to move to America. For Monica, this included her mother, father, and siblings.

Though this was a difficult change, Jennyfer and Monica’s family had to find more ways to support themselves, and the United States provided more work opportunities than Guatemala did.

“There are jobs in Guatemala, but they pay more here,” Jennyfer said. “What you can get in a week here, you can get in a month in Guatemala.”

Jennyfer and Monica’s aunts and uncles already lived in the U.S. and brought them to Gloucester where they would start their new life. With two languages already under their belts, these two were ready to take on high school in a different language.

But learning English was harder than they thought, and the language barrier has caused daily struggles ever since their families moved here.

Because she lives almost two miles away from Gloucester High, Monica takes the bus to school every day. But on the way home, she has to walk even though there is an after-school bus. “I don’t know where it’s going to go,” Monica said. This small but extremely inconvenient struggle is just one of many that multilingual students face every day.

Different backgrounds have kept these two from connecting with American-born peers, who are most of Gloucester High’s student body.

“They don’t know us,” said Jennyfer. “We have different traditions, cultures, and languages. We’re very different.”

For Jennyfer, even her connection to the church was something she left in Guatemala. After her family moved, she went from going to church on Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays to not going at all.

After school each day, the two girls head to their jobs — with Jennyfer going to McDonald’s while Monica walks to Market Basket. “We came here to earn money,” Jennyfer said. And they are– each works around 30 hours per week.

But there is so much in Guatemala that they are missing. Jennyfer especially misses the food her family makes, like the fresh pollo (chicken) that they kill and cook themselves.

For Monica, it’s the people. “I miss mi mama,” she said.

In school, they stick together, never letting the other walk to Biology or Computer Aided Design class alone and joking in Q’eqchi’ all the while.

After a few years, these two hope they can return to a place where the sounds are a bit more familiar.

“We’ll go back,” Jennyfer said. “Someday.”

Read the first three stories in the Breaking Barriers series:

What We Can Learn From the Multilingual Students of Gloucester High

![The Volleyball team poses after their win. [Photo courtesy of GHS Volleyball]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_6936.jpg)

![The GHS/MERHS senior cross country runners pose together on Senior Night. [Photo courtesy of Manchester-Essex Athletics]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-10-at-11.18.29-AM.png)

Sally goldenbaum • Apr 21, 2025 at 11:38 am

Thoughtful, informative and so insightful!