We live in an age of stories.

From BookTok to the news media to Instagram posts, we are in a digital age run by and on storytelling: the narratives and worlds we construct and live within, the structures on which we build our ideas about the world. Now, as the entertainment industry morphs into an ever-running machine of content-creation, we are in an era of discussion: whose stories are whose to tell? What do we, as creatives, writers, and artists, have claim to? Where is the line between representation and overstepping your cultural bounds?

In preparation for Oscar night, I watched “American Fiction”, the award-winning film about Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, a black author and academic, and his struggle with both his personal problems and his artistic ethics as he becomes fed up with the entertainment industry’s treatment of the black community. Monk hails from a highly privileged New England background, and jokingly writes a stereotype-ridden book he titles “My Pafology” after his previous ultra-esoteric novels fail to make him any money. The movie focuses on his personal journey with his complicated family in the wake of tragedy, with his publishing misadventures earning him funds to support his loved ones.

“My Pafology”, later renamed “F*CK”, is published under Monk’s pseudonym, Stagg R. Leigh, a made-up fugitive on the run from the law. The book is riddled with caricatures of black Americans, references to the crack epidemic, and rampant gun violence.

“American Fiction” brings up a host of fascinating questions about artistic boundaries and their limits. As a wealthy black man, is it acceptable for Monk to write a satire about the struggles of impoverished black Americans and the stereotypes they are subject to?

As new writers, we’re often told to “write what you know”. Meaning, when creating a story, pull from your own real-world experiences. This helps stories to feel authentic and genuine, as those with first-hand experience in an area often offer a unique perspective that those on the outside are not privy to.

But “write what you know” can only get you so far.

A similar racial conundrum is presented in the book “Yellowface”, by Chinese-American author R. F. Kuang. “Yellowface” follows a white author, June, after she steals her deceased friend’s novel about the Chinese Labor Corps, completes it herself, and publishes it under her own name. The book follows June’s thrilling and sinister journey through the publishing industry, and explores her own mental gymnastics as she tries to justify her own wrongdoings.

Athena Liu, the dead friend in question, is an effortlessly cool and hyper-privileged Chinese-American author, unfathomably successful and unable to fail. The book explores the ethics of a white author telling a distinctly Chinese story, and also the ethics of Athena’s own writing, as June relays to us stories of Athena taking advantage of the people in her life for writing material.

Is June at fault solely for telling a story that belongs to a culture outside of her own? Not necessarily. Plenty of authors successfully include characters who are marginalized in a way the author is not. R. F. Kuang’s fourth novel, “Babel”, includes characters from a wide range of backgrounds, from Indian to Irish to Haitian.

R. F. Kuang clearly does her research when writing these characters, for one key reason: she is aware of the tropes she is writing around. A Chinese-American author like herself writing a black character has to do extra work to be aware of the stereotypes at play narratively, because otherwise she runs the risk of writing an offensive caricature. In “Babel”, an anti-colonialist fantasy novel set in England, Kuang is hyper-aware of not reducing her BIPOC characters to disposable plot devices existing in service of a larger white-centric narrative, making them their own individuals with autonomy and needs.

Every storyteller should make a genuine and concerted effort to represent a wide range of human experiences and realities in a story—narratives where every character is the same often fall flat. But human beings cannot write about things they have no knowledge of: in that sense, it is impossible not to “write what you know”. Therefore, when you are unable to “write what you know”, you must expand what you know.

Research is a key component of good writing. To accurately represent a people, it is necessary to connect with and learn from members of their community. In this sense, “write what you know” does not confine us as artists to their our limited experience—rather, it compels us to better our understanding of the world.

It is important to note that research does not automatically make art accurate or representative. Inevitably, if you are an author writing about experiences that are not your own, something will be inaccurate: seeking perfection when writing is a doomed path. Research is a tool that allows us to briefly inhabit the realities of others. To write a novel necessitates learning, making an attempt to educate oneself and accepting criticism for where one comes up short. The quality of one’s research is reflected back in their writing: if you approach your learning from an exploitative angle, absent of genuine curiosity and care, the work will reflect it.

Of course, works of art are not always aiming for accuracy. There is a marked difference between the two controversial works at the center of “American Fiction” and “Yellowface”: namely, that one is a satire and one is historical fiction.

In “American Fiction”, Monk agonizes over whether or not his satirical book perpetuates negative stereotypes about black Americans. After all, the satire of “My Pafology/F*CK” is only effective if the in-universe audience can pick up on the fact that it’s satire in the first place, since Monk writes it under a pseudonym and markets it as a memoir.

Satire is a far less tidy genre than straight fiction. The original controversy in the book “Yellowface” begins in earnest when readers begin to pick out June’s implicit racism woven into the stolen manuscript that she heavily edited to make more palatable to a white audience. The problem that the in-universe readers latch onto stems from June’s own lack of awareness of anti-Asian stereotypes and narratives, and her refusal to hire a sensitivity reader (which causes an entire separate in-universe conflict: this book is chock-full of controversies).

When assessing a work for cultural appropriateness, it is crucial to consider the author’s goal. Generally speaking, the goal of a genre like historical fiction is to represent and capture something essential about the world. Sometimes this necessitates factual accuracy, and sometimes entertainment value is prioritized above hard data—the show “Bridgerton” is a good example of this. Regardless of your goal in terms of factual accuracy, research is still necessary to, at minimum, avoid writing caricatures. This is precisely the reason satire is tricky, as in satirical writing, caricature is often the goal.

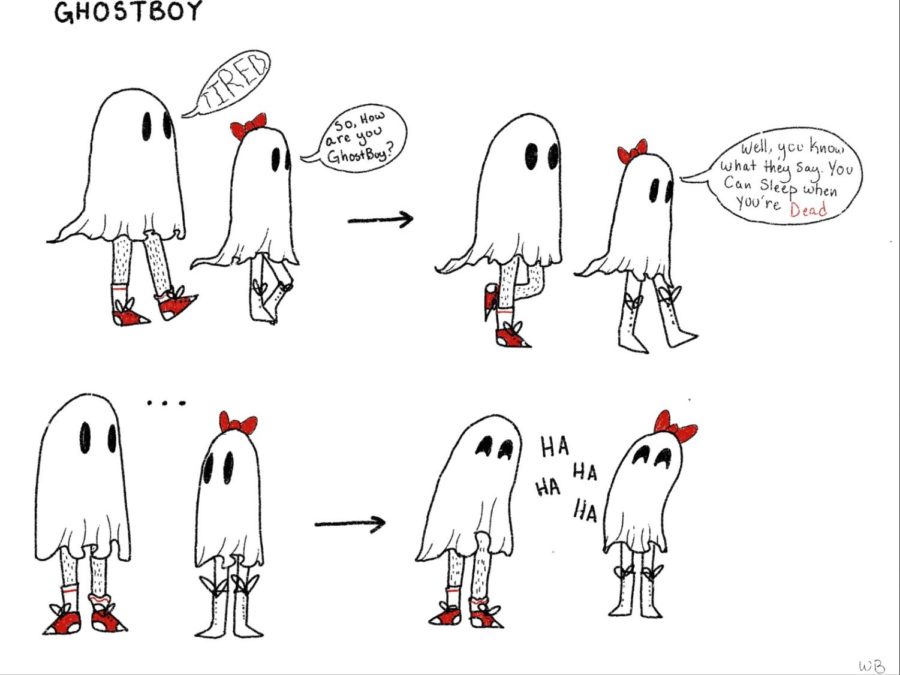

It is not necessarily the artist’s responsibility to edit and curtail their own work to account for the negative side effects stemming from the people who misinterpret it. Often, it is not the goal of the author to make the satire easily identifiable as satire—indeed, works of satire often suffer as a result of trying too hard to include the audience in the joke.

Of course, good satire is aware of the stereotypes it is writing around. Bad satire feeds into these stereotypes without effectively critiquing them, acting more as shock-jock comedy than effective social commentary.

The question with satire is whether or not research is enough. Can a straight person immerse themselves in the queer experience enough to gain the insight necessary to write satire about it? Is satire without individual lived experience and insight as effective, or effective at all?

I don’t have the answers to these questions. Nor, I would assume, do most people. The wonderful thing about writing is that individual writers can figure out where their own boundaries are, and experiment with them. And while it’s crucial to think about the impact of one’s own writing, trying to anticipate and address every critique before receiving it is madness.

Writing is an exercise in capturing something essential about the human experience and reflecting it outward. Whatever shape that takes is up to you.

![The GHS/MERHS senior cross country runners pose together on Senior Night. [Photo courtesy of Manchester-Essex Athletics]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-10-at-11.18.29-AM.png)

christy uhrowczik • May 16, 2024 at 9:05 pm

So enjoyed reading about these contrasts and all that helps tell a good story. Amazing insight! Loved American Fiction and can’t wait to read Yellowface! You are a gifted writer dear one!