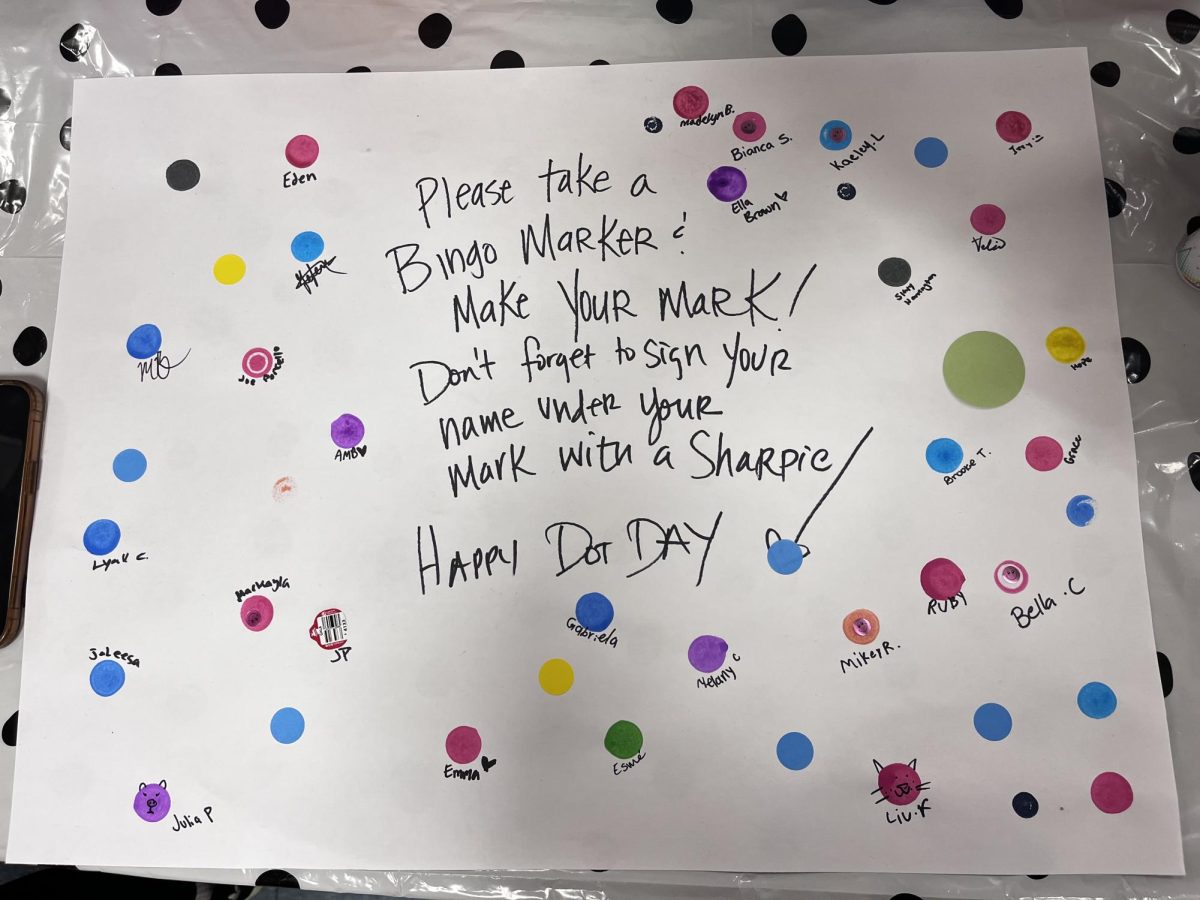

Esperanto: the newest language you’ve never heard of

An illustration of the offical flag of the Esperanto language.

Throughout history, the increase in international relationships has led to a question – how do we communicate with someone we don’t share a language with? How do we form friendships, deals, treaties, from behind a language barrier? Some use captioning, some use translators, and a few advocate for an entirely new solution: Esperanto, “the international language”.

As of 2022, there are over 7,000 languages spoken globally. Within each language, there are dialects, creoles, pidgins, variations that make learning a language far more complicated than most have time or energy for. International conflicts have begun due to mistranslation – a single word off, and a demand could be construed as a threat.

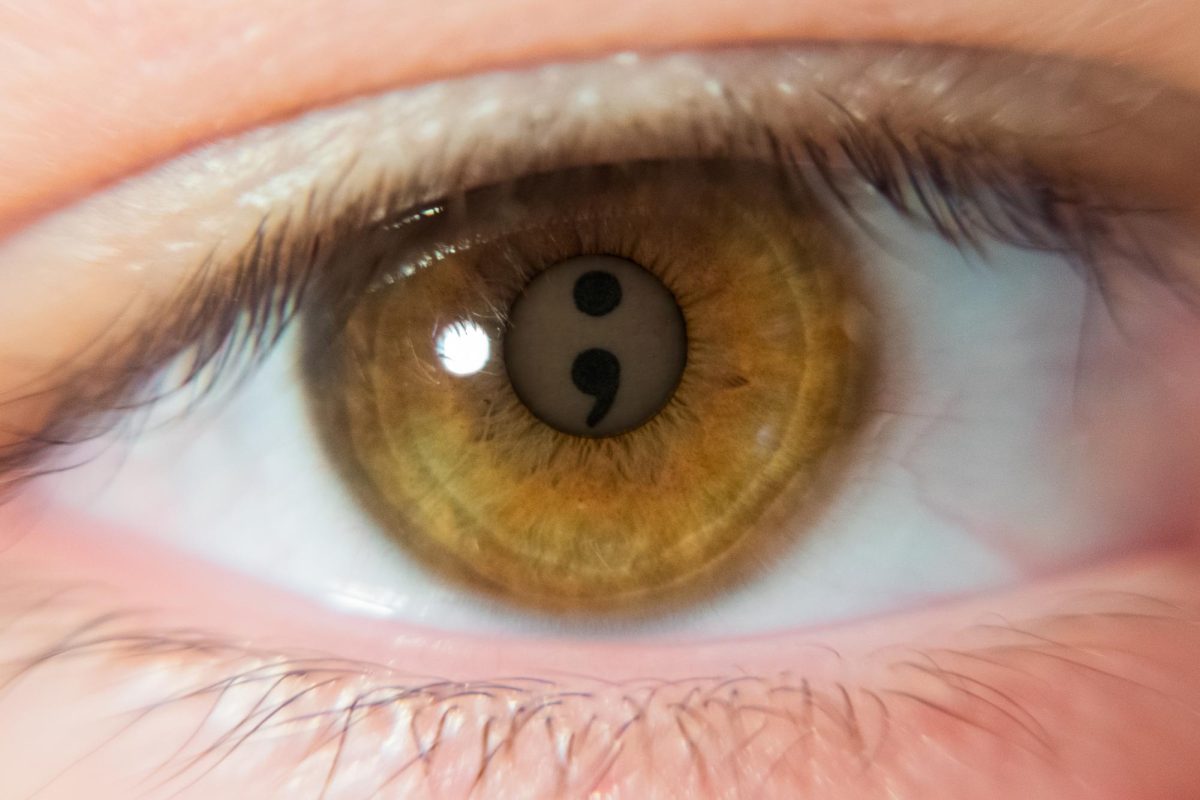

So, in the 1870s, an ophthalmologist named L.L. Zamenhof came up with a solution, a language of his own invention that could become the world’s common language – Esperanto.

Zamenhof was born in Russian-occupied Poland, in an environment where German, Yiddish, Russian, and Polish speakers could be found living on the same block. Zamenhof felt that the language barrier was the cause of much of the tension and fighting between these groups, and set about devising a neutral language of his own. Zamenhof’s pursuit is noble in nature, few may argue against that. Esperanto was invented to be a go-between, a language without cultural connotation.

Esperanto is spoken worldwide, though most commonly in Europe and East Asia. There are an estimated 1,000-2,000 native speakers, and around 100,000 who use it regularly. Though this is far from Zamenhof’s initial goal of global usage, it is the most widely used constructed language in the world.

The central benefit of Esperanto lies in its simplicity. In English, the verb “to go” is “go” in the present tense, but “went” in the past tense. This is because they used to be two verbs – “to go”, and “to wend”. The past tense of “wend” was “went”, and the past tense of “go” was “gade”. Over time “wend” fell out of fashion, leaving behind “go” and “went”.

That semi-bewildering example illustrates something key about languages – they change drastically over time. The longer a language exists, the more its words blend together and fuse into new words, making it difficult to learn. Esperanto is less prone to this phenomenon – having only existed for about 150 years, as opposed to English’s 1500+ years. Zamenhof understood the difficulty of learning a new language well, and designed it to be simple. Associates of his who adopted the language sang its praises – some claimed that with intensive study, one could become competent in just 3 months.

But there are two central issues with Esperanto – two that cannot easily be ignored.

The first is its inherent Eurocentrism. Esperanto is largely structured like a Romance language in terms of vocabulary, and its syntax is glaringly Slavic and Germanic. It uses the Latin alphabet, and the sounds made by the accent marks are decidedly easier for an English speaker than, say, a Korean speaker. The whole “competent in 3 months” thing may apply to someone who speaks Czech, or Romanian, but what about Vietnamese? Telugu? Urdu? So, it seems that Esperanto may be a Western solution, not an international one.

The second, a popular, and admittedly sensical argument against the widespread use of Esperanto, is that English has already filled this role. In Europe, the majority of the north speaks both their mother tongue and English. English is taught in schools worldwide – countries like Japan will even pay to have English teachers come to their country and teach English. English is becoming “the language of the future” as it continues to dominate online spaces, political spaces, artistic spaces.

But there is a problem with this – cultural connotation.

English is the language of colonizers. In the span of a few centuries, Britain managed to colonize 25% of the world, bringing in the English language as a requirement and wiping out countless indigenous languages. English being the world language is, although true, not necessarily a good thing or something we should settle for. Disagree if you wish, but the fact of the matter is that the world language being English is not accidental, or due to any particular benefit of the language itself – it is because British colonization succeeded.

But is Esperanto any better? And, equally importantly, is it practical? Would having a constructed language rather than a pre-existing one as the default really change anything?

The question of Esperanto’s usability is complicated, and it’s unlikely that it’ll ever be widely used. However, it raises a lot of interesting questions. Is there a solution to the language barrier? How do we unify ourselves as humans linguistically without putting our cultures in danger?

Aurelia Harrison (they/them) is a senior and Editor in Chief for the Gillnetter. Their interests include writing, thinking about writing, music, and talking....

Cyan Clements is a senior at GHS and is a second year writer for The Gillnetter. She is a honors student and takes pride in being the resident artist for...

![The Volleyball team poses after their win. [Photo courtesy of GHS Volleyball]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_6936.jpg)

![The GHS/MERHS senior cross country runners pose together on Senior Night. [Photo courtesy of Manchester-Essex Athletics]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-10-at-11.18.29-AM.png)

![The Volleyball team poses after their win. [Photo courtesy of GHS Volleyball]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_6936-600x476.jpg)

Kutimul • Oct 29, 2022 at 12:14 pm

Esperanto wouldn’t be better than English… Which country did Esperanto speakers colonize? And could you name any country having Esperanto as a national/common language?

Esperanto’s etymology may be almost entirely Indo-European, however its grammar is not. Its grammar is closer to the one of an isolating language, like Chinese.

And this is why Esperanto is popular outside Europe and the Americas: many speakers come from Iran, China (actually China Radio International has an Esperanto version, and Esperanto can be learned at schools and universities in China), Japan, Korea…

Esperanto isn’t perfect ofc, but it would clearly be a much fairer solution for everyone on this planet. Refusing to accept that means letting linguistic discrimination and linguistic imperialism continue.

Johannes Genberg • Nov 5, 2022 at 5:38 am

Esperanto is an agglutinative language, which is closer to Finnish, Japanese or Turkish. I don’t know why you call it an isolating language, because it clearly isn’t.

Frano • Nov 12, 2022 at 7:44 am

For those who are interested in the classification of languages, I can suggest referring to the article by Claude Piron “Esperanto: european or asiatic language?” I am not a specialist in linguistics, so I will not evaluate the arguments given there. From my own experience, I can only say that from a practical point of view, Esperanto is an effective tool for international communication, especially in the Internet Age.

Frano • Oct 27, 2022 at 5:58 am

The title of the article surprises in the 21st century. Perhaps 130 years ago this was the case. Has nothing really changed and Zamengof’s proposal is still “an entirely new solution”?