The hot Central American sun beats down on a grassy field in the village of Tikal Futura, Guatemala. Clouds of dust form in the air, kicked up by six eight-year-old boys running after a dirty white ball. The boys pant with exhaustion and sweat drips into their eyes, but Alejandro Arreaga doesn’t notice the heat as the ball is passed to him. Surrounded by his childhood best friends, Alejandro smiles as he prepares to take a shot at the goal. With all the strength his second-grade legs can muster, Alejandro kicks the ball, and it soars into the net.

“I grew up playing soccer,” Arreaga said. “It was the first thing I loved.”

Before he moved to the United States, soccer was Arreaga and his friends’ favorite activity.

“It’s like tradition for us,” he said. “It’s something important you can never forget when you grow up.”

Nine years later, a referee’s whistle pierces the evening air. It is Gloucester High’s championship game, and Arreaga’s cleats dig into the turf as he sprints down the field. He gets the ball and expertly delivers it to his teammate, who shoots and scores.

As his teammates erupt in cheers and gather around, Arreaga knows he has found a sport he will play forever– no matter what country he is in.

Arreaga brings the same enthusiasm to the field as he did when he was a kid in Guatemala, even if he is four thousand miles away from his best friends.

Growing up, Arreaga lived with his sister, brother, and father. Arreaga and his sister moved to the United States when he was only eight, four years after their mother did.

The main reason they moved to America was so they could get a better education. But before he could understand what his teachers were saying, Arreaga faced the challenge of learning English — a daunting task, since he hadn’t learned a word in Guatemala.

“It’s hard to speak English as a second language,” said Arreaga. “It took two years before I could communicate in English.” Becoming fluent took at least three or four.

Now, nine years later as a junior at Gloucester High, Alejandro’s understanding of multilingual students’ struggles helps him give back. As an immigrant himself, Alejandro knows the challenges they face because he did, too.

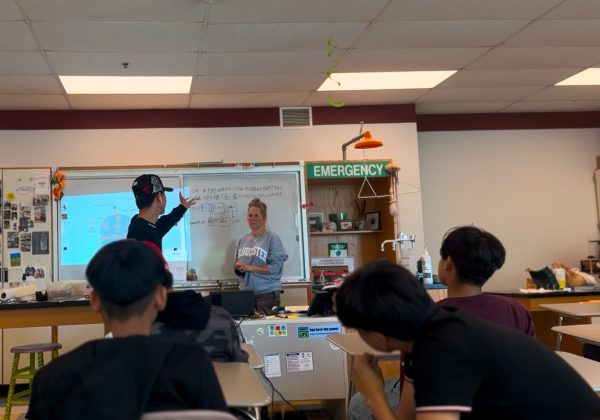

Jessica Lichtenwald, a biology teacher, taught Alejandro as a student when he was a freshman. But it wasn’t until his junior year that she realized his ability to bridge gaps between multilingual learners and their teachers.

“It happened by accident,” Lichtenwald said. One day, she was teaching biology to a class of English learners when Alejandro stopped by for a visit. “I must have asked the kids a question, and he said it in Spanish. Then, I was like, ‘I have another question, can you help with that?’”

In Lichtenwald’s E Block class of students from Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras, Alejandro helps out most days by translating lessons and directions.

“I like to help kids figure out stuff,” Alejandro said.

He also serves as a role model for these recently immigrated students.

“If they see Alejandro being successful in helping a teacher teach a class, it’s gonna show them that they can achieve, too,” Lichtenwald said. “Because he came here not speaking the language, when they have somebody that has sat where they’re sitting and they’re getting help from that person, it’s motivation.”

English Language Liaison Vanessa Lindberg believes peer mentors can positively impact classes of multilingual students.

“They connect in a way that [adults] can’t, and so it is very valuable,” she said.

According to Lindberg, who has worked with Arreaga numerous times over the past three years, his extroverted and “magnetic” nature makes him perfect for this job.

“He’s a good kid,” said Lichtenwald. “[My students] feel comfortable with him, as he’s able to relate to everybody in the class.”

Arreaga brings this positive energy to both the classroom and the field. Though he struggled to learn English upon first moving to America, Arreaga said he always found solace in soccer, a passion since age seven.

In 7th grade, he joined the Gloucester High soccer team. An extreme extrovert, the skilled midfielder said his favorite part about playing on the team is that, “You can know people from different countries. There are Colombians, Mexicans, and Venezuelans.”

Arreaga hopes his passion for the sport will carry him to a collegiate team– and possibly even further.

If everything in his life goes according to plan?

After high school, he wants to play for “my dream college, which is UMass.”

At UMass, Arreaga hopes to study finance. Learning about money management reflects his desire to help others, just like he does through peer mentoring.

“I would like to study for my family,” he said. “I want them to have a better life. Things we didn’t have in past years, we can have in the present.”

After UMass, Arreaga would like to play for a soccer club. Then, he hopes to go pro.

“I would like to play for the national team of Guatemala,” Arreaga said. “As a kid, it was my first goal.”

But there’s another reason he is so passionate about the game. In 2015, shortly after Arreaga had left for the U.S., his older brother Marvin passed away in Guatemala.

Alejandro’s best times with his brother were on the soccer field. When asked if he has any specific moments, he remembers: “I have just one,” Arreaga said. “We used to play soccer for the same team, and he got the MVP as one of the best strikers.”

Arreaga said, Marvin advanced enough to play for the Youth National Soccer Team of Guatemala.

But then, tragedy struck: Marvin was shot and killed.

“He was 15 years old when he passed away,” Arreaga said.

Now, Arreaga will bring a little bit of his brother with him each time he steps on the soccer field, whether it is in high school, college, or beyond.

“My family wants me to play for a pro club or somewhere they can see me in the big leagues,” he said. “They want me to live a legacy on the soccer field to honor my brother.”

Read the first four stories in the Breaking Barriers series:

![The Volleyball team poses after their win. [Photo courtesy of GHS Volleyball]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_6936.jpg)

![The GHS/MERHS senior cross country runners pose together on Senior Night. [Photo courtesy of Manchester-Essex Athletics]](https://thegillnetter.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-10-at-11.18.29-AM.png)